Would You Still Follow Me If I Was a Worm?

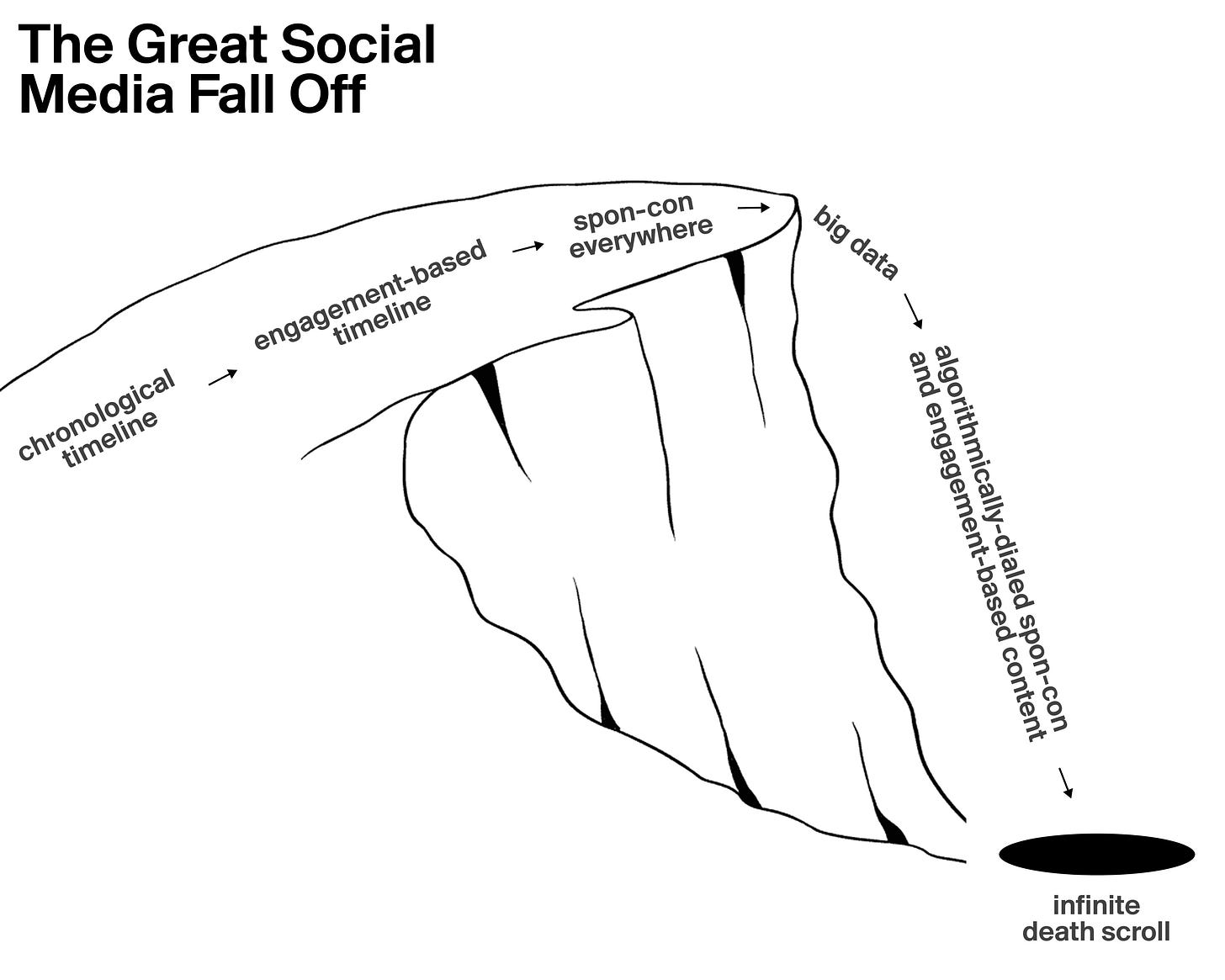

The Great Social Media Fall-Off

Findings is a monthly newsletter on the influences and trends that are quietly shaping our culture by Mouthwash Studio. This post may be too long for email, read online for the best experience.

If this was forwarded to you, consider subscribing for future posts.

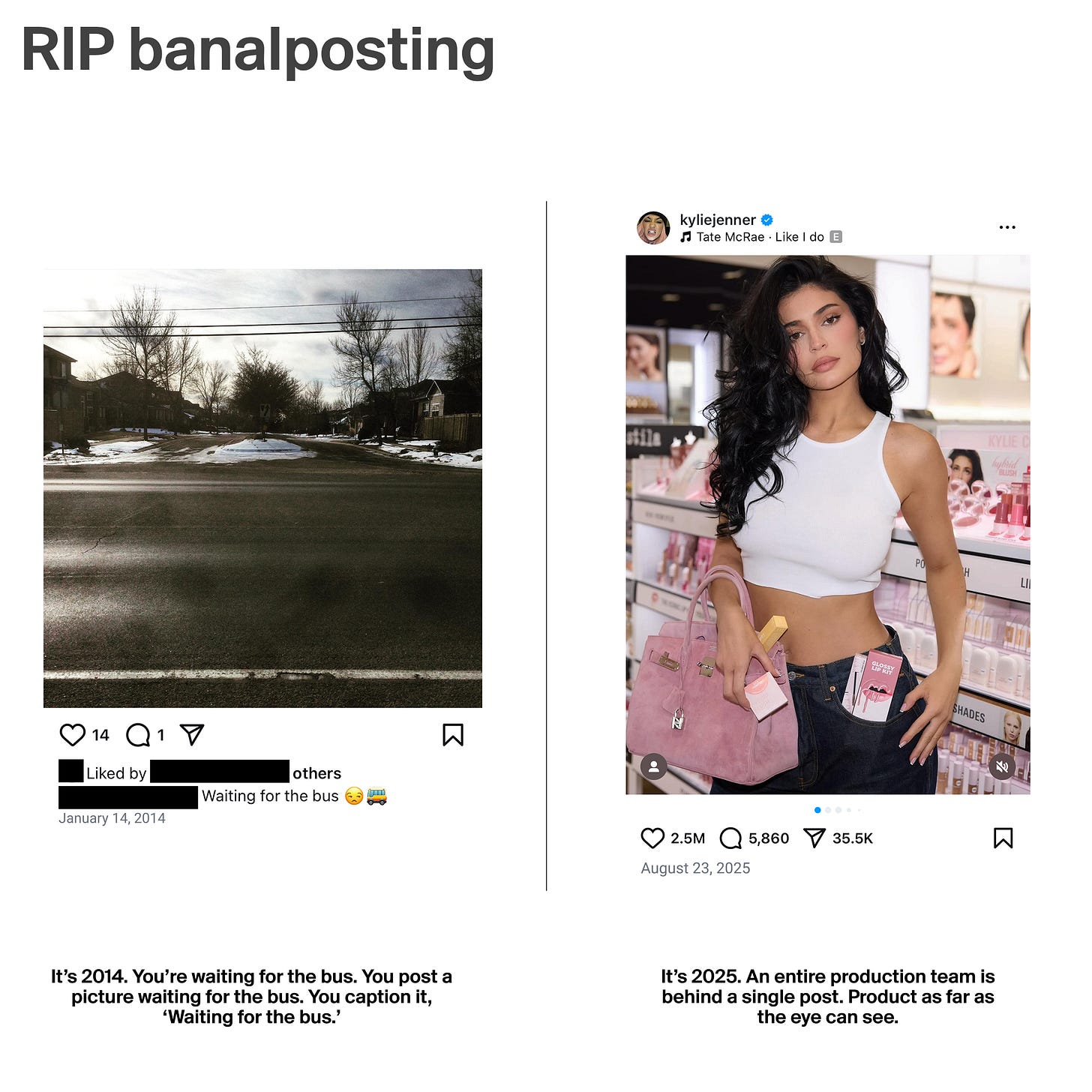

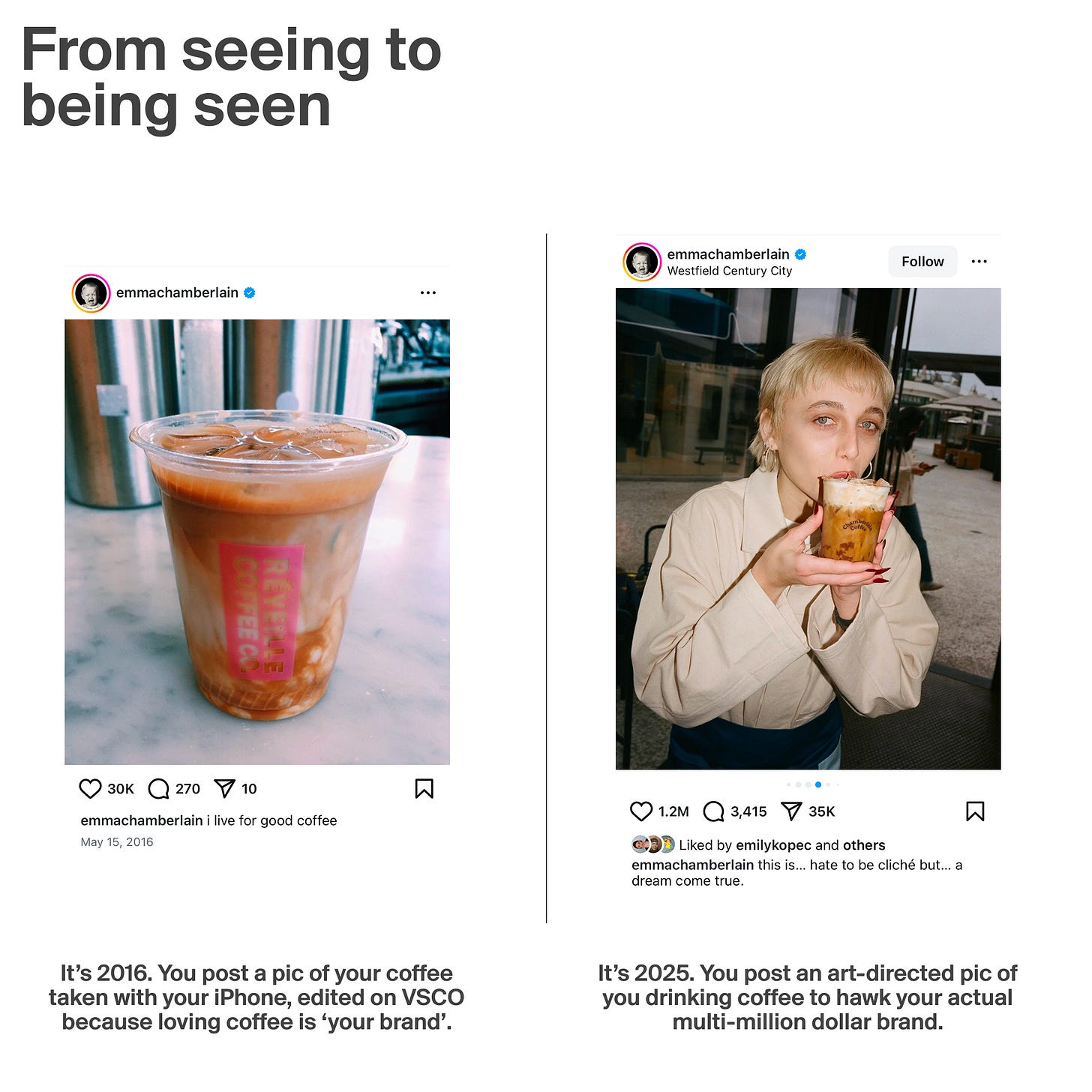

‘Social media’ has become a misnomer. What once served as a sort of visual record of existence (no matter how banal1) has become home to the highest ad spend of any media channel2.

Along with this shift from the personal to the commercial, it doesn’t take much to dually note a shift in perspective—from sharing one’s observations, to sharing oneself for observation.

While these shifts haven’t totally eclipsed the social function of media networks, they certainly have strained it. On the incumbent platforms, anyone is welcome to scroll forever through what can feel like mostly commercials.

Some tap in. Most of us tap out.

Today, brands exist across the widest spectrum we've ever known — personal brands, small brands, mega corporations. Regardless of scale, the shifts presented above put us in the middle of a dilemma where everything is legible as promotion, creating a layer of quiet suspicion across nearly every interaction. As consumers, we’ve trained ourselves to scan for motive, read between lines, and ask not what is being said but why it’s being shown to us at all.

I. If Hawkins Were a Place

Somewhere along the way, the social internet slipped into its own inverted version of reality. We still have profiles, feeds, conversations, but the physics of these digital spaces have changed. Expression and advertising now share the same surfaces, the same incentives, and the same language. What was once observational is now performative.

I lost the plot of Stranger Things after Season 2, but finished it anyway after a 10-year run. The guinea pig for the Netflix effect worked on all of us, and what was truly a genuine and innocent story in its earliest years turned into a hyper-sensory series of Marvel-adjacent visual junk food. Next episode in 10, 9, 8….

In the show, the Upside Down is a parallel world that mirrors the characters’ hometown almost exactly, but is rendered hostile — a familiar world filled with monsters, flickering signals, and failed communications. Both the characters and the viewers know you can survive there, but your time is limited.

As a result of a gradual series of structural changes, we may now be living in a digital version of the Upside Down. And while these changes in isolation have felt benign, they’ve ultimately rewired how our attention moves, how interaction works, and who is incentivized to speak.

So, how did we get here?

Running in place

A usual suspect for the point of no return is Instagram’s 2016 shift from a chronological timeline to an engagement-based timeline. This subtle shift acutely altered the collective scrolling experience and many users’ posting motivations. What had previously been an open-ended platform for user-generated media suddenly seemed to favor certain types of content. For example, image carousels that start with a selfie and then show all the seemingly less engagement-farmable content. The youth call them dumps.

While it feels easy to blame ‘the algorithm,’ it’s hard to say whether algorithmic feeds trained us to react to particular kinds of content, or if they more efficiently started serving us what we already engage with. But that’s a line of inquiry for another day.

We’d be remiss not to mention how sparingly, if at all, teens and younger Zoomers hard post on platforms like Instagram3. The rules of engagement have changed, and going back to the ‘way things used to be,’ just isn’t realistic (or necessarily desirable!) for the newer generations.

Still, it’s clear that one of the biggest repercussions of the shift in timeline structure has been the inconspicuous fusion of social currency and cold, hard cash, recalibrating the way we interact with one another online, and probably, in person.

Is this thing on?

With the dawn of social networks came a near-utopian promise of unprecedented and unmitigated peer-to-peer engagement. While relationships have undeniably been forged and fortified through social, the medium also undeniably altered those processes by blurring the line between the public and private spheres: to reach one, you need to first reach many.

Despite its name, social media has become a sort of neobroadcast media. Perhaps it only ever masqueraded as anything else. The implications of this are intuitive, much discussed, and need hardly to be examined here.

If all the world were a stage in 1599, it certainly is only more so today.

Who does the hawking and how?

A medium of communication that connects one to many is perfectly designed for getting the word out: on cultural, political, or commercial matters, among others. Such a medium is suited to what are essentially announcements, which, in turn, constitute the traditional form of advertising: one big message, for everyone to see.

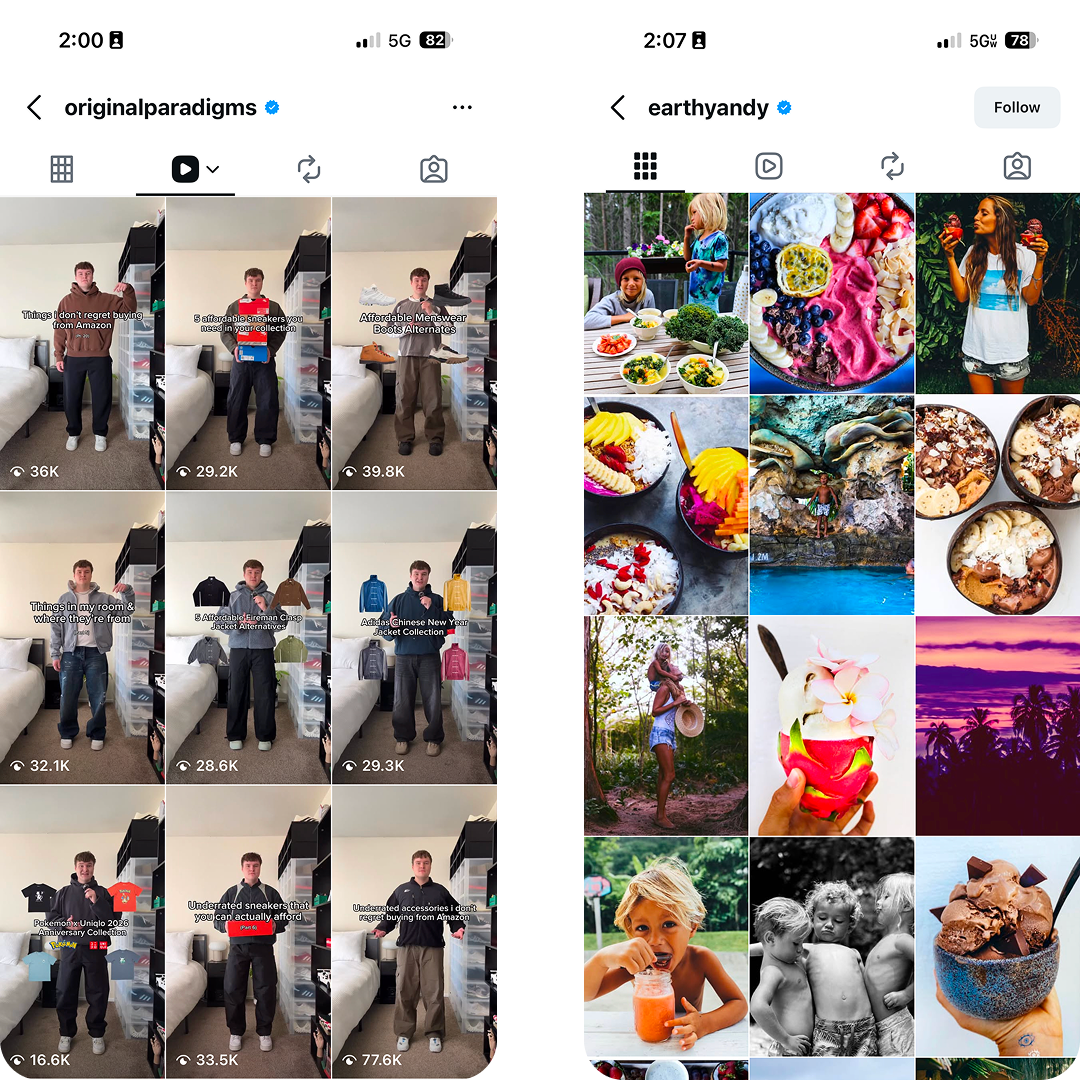

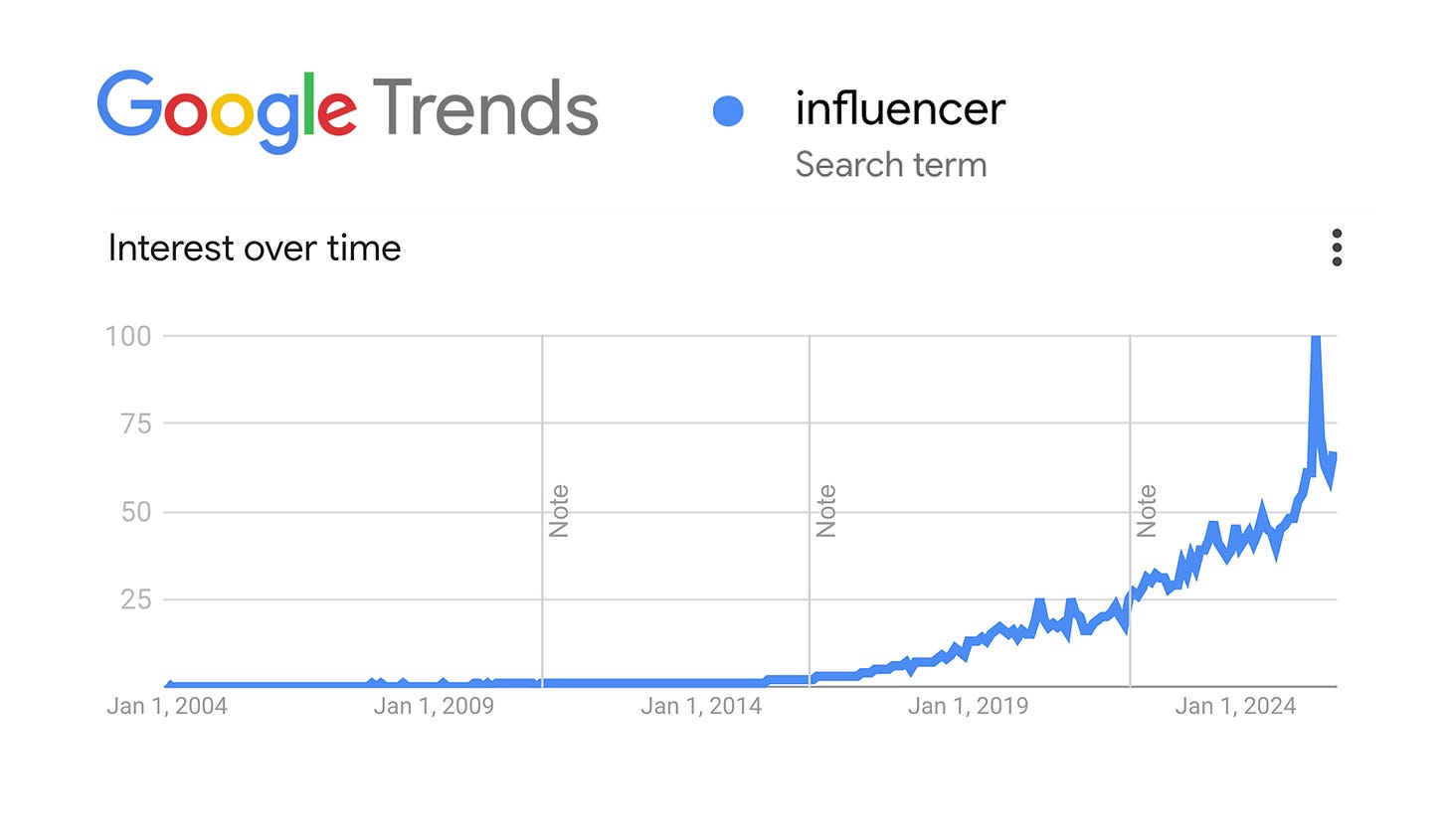

The phenomenon of social media didn’t really change the communicative model of advertising; rather, it changed who participates in it and how. When the term ‘influencer’ made its way into common parlance around 2016, it was both ridiculed and embraced in equal measure. Now, the profession is real as ever, perhaps made even more so by the oft-cited 2024 statistic reporting that 57% of Gen Zers want to be influencers4.

This generation-wide aspiration to influence seems almost inevitable once we consider that the distinction between the ‘influencer class’ and the general population has long since begun to fizzle.

Although the company shuttered just a few months ago, the underwear brand Parade was a pioneer in brand-building through micro-influencer strategies, sending free items to people whose follower counts were around one to several thousand—well below those of your traditional influencer.

Regardless of the brand’s long-term success, what the case study makes clear, is that somewhere along the way, it became a given that anyone can be an influencer. And when an opportunity bears itself, tech tends to jump on it. With the advent of TikTok Shop (which generated $33 billion U.S. dollars alone in 20245) and Amazon Storefronts, it’s endgame. We’ve reached the age of the proletariat influencer. The pleb-fluencer. The everyman-fluencer. The you-and-me-fluencer.

The influencer bubble will inevitably burst. Hence, you can survive for now, but both the characters and viewers know that our time is limited.

II. What’s Worth Making?

These forces have all converged into our strange inverted reality, a major implication of which is a general sentiment of exhaustion and cynicism among audiences. The age of unprecedented reach has created a reluctant audience.

But in that cynical and jaded crowd, we see less of a lost cause and more of a petition for us to meet the moment. If brands continue to populate our social spaces, they need to get back to the basics — back to a principle so fundamental it’s easy to forget: a brand should provide value.

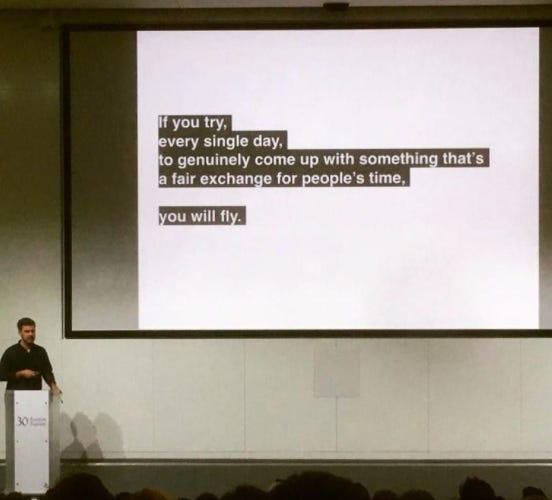

In a world of information overload, value can be defined as easily as a fair exchange for somebody’s time. The most compelling brands today give their audiences something meaningful online. And that exchange regenerates as brand value. On the other hand, brands and individuals that don’t question what value they’re providing simply make noise in an effort to not be forgotten. But this kind of noise is inevitably and ironically forgettable.

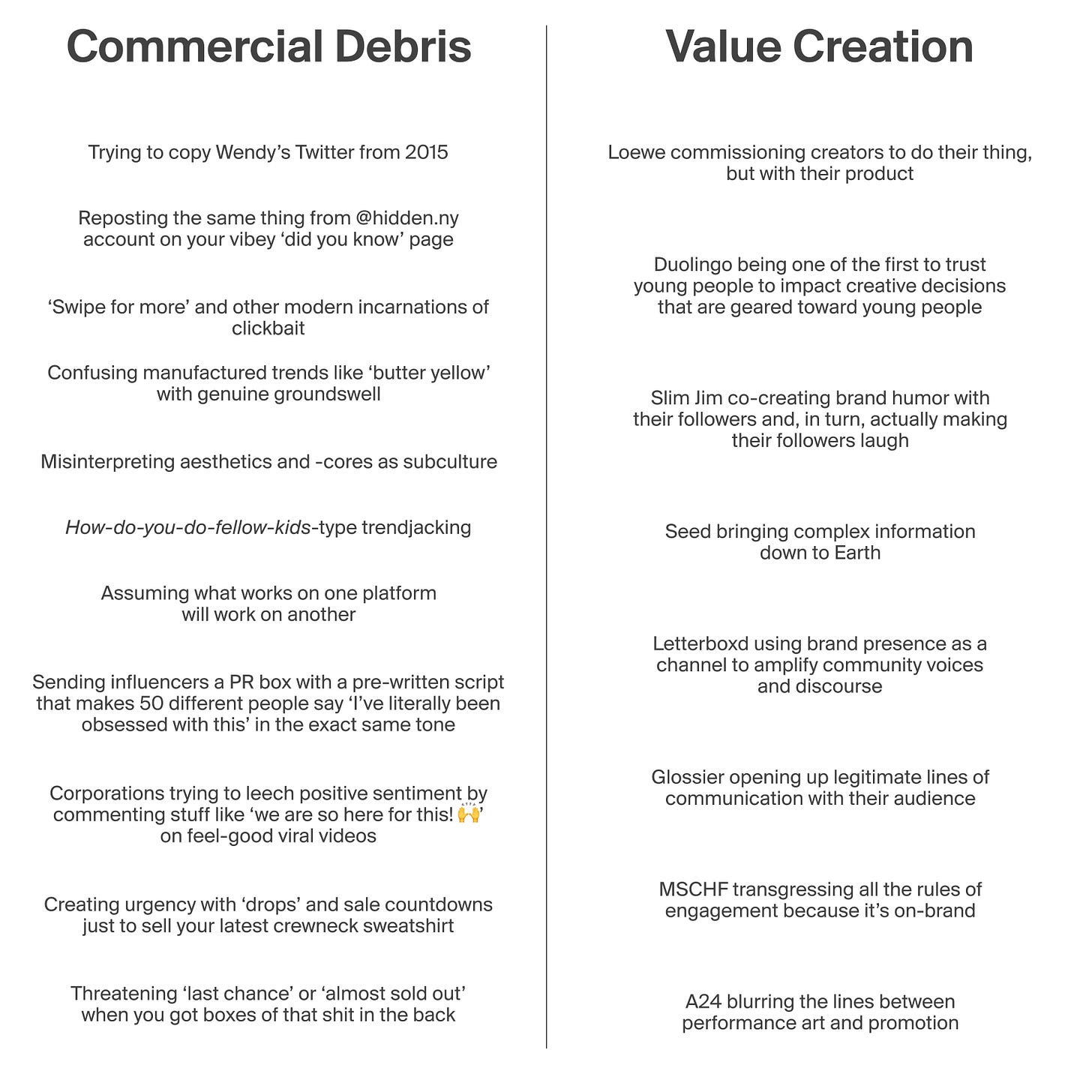

We call it Commercial Debris.

We also spoke to a number of industry peers to find out what they expect from the brands they follow on socials. The answers were affirming, but left us all a bit loath to acknowledge the fact that few of us are actually delivering on our digital longings.

“Give me something of value. My feed is highly curated, and I don’t have time or headspace for superfluous or superficial shit. Feed my brain, show me something new, give me something to think about, make me laugh, stoke my imagination.”

- Strategy Director on what they want from brand socials

Value doesn’t have to look one way. In fact, it shouldn’t. But zeroing in on a meaningful manifestation of brand value requires vision and a concerted allocation of time and energy. And seeing the resulting payoff takes patience. It’s not a quick-and-dirty investment. It’s a concentrated effort to craft a distinct perspective, to build relationships, to contribute something meaningful to a world that is increasingly cluttered and slop-ridden.

This effort is one that brands that actually care about making something worthwhile are entirely on the hook for. And there are tons of ways to go about it. Today, we see attempts playing out across a spectrum of high signal to low signal (indicating the potency and lingering impact of social behaviors), and from self-serving to audience-serving (indicating whether brand-centrism or audience-centrism is the driving force behind their social footprint).

Brands in the top left quadrant provide value through magnetism and restraint — they preserve a polished image, a benchmark for aspiration, while still pulling people in. But it all starts from the brand’s directional conviction.

Brands on the top right find their draw in a more reciprocal audience relationship — inspiring, informing, and sometimes taking a backseat to let people, partners, and ideas lead. Such social footprints often feel less like marketing and more like a true point of view. These brands accrue trust slowly, but that trust compounds over time.

Brands in the bottom right succeed by meeting the moment. They entertain, they relate, they express cultural fluency. But ultimately, they give people a moment, not a perspective. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Low signals die out quicker and carry less substance, but reputation is earned through consistency. This is an approach that requires upkeep, perennial reinvention, and small but frequent risk-taking.

The bottom left quadrant is the dead zone. Weak signaling, weak audience engagement, and weak brand impact. It’s content made to fill space and attract attention without respect for that attention. When brands optimize for visibility rather than value, mistaking presence for relevance, they start churning out Commercial Debris. It’s an easy trap for brands to fall into. But for every point, there’s a counterpoint.

III. How to Fly

Intention is a good starting place for most things in life. This new ‘social’ reality has distracted brands into going for awareness point blank — a play whose winning days are running dry.

Intention, then, means understanding that socials are little more than communicative infrastructure — an infrastructure whose possibilities feel infinite, but whose popular usage by commercial entities has felt like a catastrophe in slow motion. The glorious internet has given brands another playing field in which to prove their worth. And that worth must be earned intentionally, strategically, and honestly.

In a debris-ridden cyberscape, now is the chance for the best brands of tomorrow to prove themselves a counterpoint.

Until the fault line beneath today’s digital infrastructure forces a paradigm shift, until the default attitude of commercial enterprises is to be good, be different, be meaningful… let there be happy exceptions.

Really appreciate your content, it’s highly informational and written in a pretty slightly poetic way. Thanks