Are We Running Out of Brand Names?

On the frustrating complexities of naming just about anything.

Findings is a monthly newsletter on the influences and trends that are quietly shaping our culture by Mouthwash Studio. This post may be too long for email, read online for the best experience.

If this was forwarded to you, consider subscribing for future posts.

The team here at Findings was recently (and painfully) reminded of how difficult and annoying it can be to try and name something. Between securing a username for Substack (s/o @mouthwashstudio1), labeling the growing verticals of the studio, and the ever-present need to put ideas into words for clients, naming is, for lack of a better term, a headache for all of us.

But like the great thinkers before us, we turn our tragedies into strategies, and so here we are.

As far as I’m concerned, naming is an act of the divine. Much like puns and random bits of trivia, some people just got it like that. In fact, later in this piece we consult some of those “just got it like that” people, aka people who have made a career out of naming, getting their ideas on the driving forces behind what constitutes a great name, and lending some thoughts as to whether or not we’re running out of brand names.

Before we get there, let’s observe some soft truths on the matter.

The perfect name, unfortunately, does not exist, and to pursue such an item would be a fool’s errand. But perfect names do exist. How does that make sense?

You’re probably reading this article on a perfectly named device right now. Brands like Apple, Liquid Death, or Homer have tapped into a certain essence, so much so that it's hard to fathom how the name didn’t exist before it suddenly did.

And that’s essentially what makes a name great.

It’s obvious, exists right outside our periphery, and has a layer of spontaneity and intrigue that stops you in your tracks. But just knowing what a great name is doesn’t make it any easier to arrive at our destination.

From the outside looking in, this ambiguity and subjectiveness around naming can be clearly felt when you look at a brand like On Running. Their recent Super Bowl push feels more like a multi-million dollar attempt to remedy an early brand mistake than it does a traditional awareness campaign. Undoubtedly, “On” is an incredible name to own and an inherent strength of the brand, but even they couldn’t have predicted that certain audiences would believe it to be “QC” instead. Regardless, we applaud the brand’s flexibility and nimble approach in their response to a sensitive subject matter.

The question of whether or not we’re running out of names for brands is in part an observation on how our societal vernacular is changing. Naming has always been a device to connect, but it remains to be seen how long this will remain undeniably true. Just like physical real estate, the digital space for ideas to take shape is not unlimited.

This line of thinking is even more pronounced when we contemplate naming in the era of ChatGPT. No longer do you need to stare at a whiteboard with 60 different naming iterations, praying for a flash of inspiration. Include a filter by trademark-availability, and all of a sudden what once was a tedious and subjective process becomes optimistic and bountiful, endless in its iteration.

If that were the case, then why aren’t we in a golden-era of naming? If anything, the opposite seems more true. Look no further than the “feel good” sector of CPG beverages, an industry that historically has relied on naming to stand out. Culture Pop, Poppi, Olipop. You get the idea. The landscape feels stagnant, with names that feel half-baked and generative to one degree or another.

But while there are proven ways into a market, sometimes the best approach is to go the opposite direction. Liquid Death was able to turn itself into a $1.4B brand by taking advantage of this naming stagnancy, flipping the convention in an equally-stifled bottled water market.

Similarly, Guayaki holds a staggering 86% of the Yerba Mate market by closely aligning itself with the ingredient, rather than the feeling of the beverage itself; so much so that “Yerba Mate” takes a significantly more amount of real estate on the package than the brand name. In normal instances this would be a brand suicide, but the approach has obviously paid off for the yellow-canned giants.

All that to say, we are not anti-generative over here. Naming generators can, and should be, an essential tool to the naming process. A way to get unstuck, to approach ideas from a new angle, to add an unexplored perspective.

But naming shouldn’t start, or end, from the query of a generator. While a generative approach to naming offers a seemingly infinite and readily-available way to crack even the toughest naming landscapes, more importantly, and the whole point of this piece really, is that it's just boring.

If we're okay with forfeiting our personal affinities in favor of ease and convenience, what's the point of naming anything at all?

Take Mouthwash, for example. Since our inception, we’ve been plagued with the question: “What’s it mean?” The origins of our name are simple and straightforward; giving new meaning to a household name that we see and say often. The “breath of fresh air” connotation felt like an added bonus to what we hoped to bring to the design space. And it works. The name catches attention, it feels and sounds unexpected, often prompting people to repeat it for themselves in an affirmation.

Outside of our own jurisdiction, brands like Loewe are putting their unclear and hard-to-pronounce name to work, leveraging its ambiguity and building brand affinity in one fell comedic swoop. While the name itself wasn’t born out of this playful desire to get people to pronounce the name more often, and instead originates from the company's founding designer, the brand is a testament that hard to pronounce or culturally-ambiguous names can work just as well, if not better, than any universal naming approach can offer.

It’s one of a kind, which you’ll often miss in favor of safer, more obvious naming structures. This feels especially true as we’ve become a more global culture. Pre-internet, it’s likely that you wouldn’t ever come across the brand in the first place if you weren’t directly invested in haute couture in one way or another. This leveling of international markets has opened the floodgates for foreign names to not only work and be acceptable, but to succeed and have a level of intrigue baked in from the get-go.

A former client of the studio, Mesura, is another prime example to look at. The Barcelona-based architecture and design studio directly translates to “measure”, but this literal translation is often glossed over, slipping under the radar in passing conversations. It’d be hard to convince any new firm to label themselves with such a universal term as “measure”, and even harder to convincingly own. But in application, it easily works without question.

Similar to Loewe, there’s a sense of “forgiveness”, if you can call it that, for brands that are founded with global or international pursuits—names take on new meaning in foreign environments—what might be simple, pedestrian, or ordinary in one ecosystem can be transformed into abstract, unique, and ownable in another.

How do we make sense of these names, then? Sure Mouthwash, Loewe, Mesura, and many others like them work, but the frameworks aren’t guaranteed. Take the same approach and try to recreate it and your odds of success are probably slim, at best. Does it all boil down to some invisible form of confidence? That these names work because they’ve proven themselves to work over time?

We sent an email to Eli Altman, managing director of the esteemed naming agency A Hundred Monkeys, with hopes to get a new perspective on the looming questions above. Aside from naming some of today’s best brands and products like Atmos for Dolby, Eero, and Inkling, Altman is an established author of Run Studio Run and Don’t Call It That, two essential resources surrounding creative start-ups and the inner workings of the naming process. More than anything though, he’s a long-time collaborator and friend of the studio, and we’re glad to be able to pick his brain on some of these musings.

While the idea that we’re running out of names for brands might make sense at a surface level understanding of how our digital real estate functions, Altman provided a different perspective:

There are plenty of words, plenty of languages, plenty of slang, and when all that fails, we can always put words next to one another or even make up words. I’ve been doing this for over 20 years and at no point have I felt out of ideas or options. This isn’t to say that naming and branding haven’t evolved or changed. Social media has changed naming. It’s easier than ever to have an international business from day one. But it’s also worth mentioning that names die. Businesses shut down all the time, and those names can find new homes. Madewell did this to good effect.

Altman makes a strong case. While it’s easy to complain about the frustrations of securing username handles and url domains, the landscape is more or less a blank canvas. When one idea meets a dead end, it’s easy enough to flip it, replace letters, translate it in a new language, or invent a new word out of it. Most importantly, names don’t exist in a vacuum. To place all of the pressure on the name to do the brand’s job from day one is an unnecessary stressor.

The job of a name (in most cases) is to get people interested—to get them to pay attention in a world where everything is vying for their attention. Names exist within the broader context of a brand and then a company, an industry, the culture. A name is just the beginning of an interaction or a relationship. From there, it’s up to the brand to keep it interesting, to deliver on their promises, to add more depth to what the name means for people.

When you put it that way, it’s hard not to question the significance we place on naming, and whether a name even matters in the grand scheme of our environments. Can a good name carry a mid product? Can terrible names be ignored if other parts of the experience make up for it?

It certainly doesn’t matter to everyone. A name is part of the gestalt of a brand. There are great names paired with terrible logos and decent products. Awful names with ok logos and great products. We’re dealing in continuums here, not binaries. There are some industries where names carry a lot more weight—like fashion or alcohol. So yes, great names carry mid products all the time. But there are also very successful companies with terrible names. Look at the Fortune 500. Nothing is a panacea here.

When asked for advice on becoming unstuck in naming adventures, Altman cites literature as a prime point of escape and inspiration:

Find a piece of fiction that relates to what you’re trying to name in some way. Read it with a highlighter and pull out interesting words and phrases. Look for things that take on new meaning within the context of what you’re naming.

Aside from heading to your local library, there are plenty of other great resources to either get started, or end your naming pursuits:

Onym is a prolific leader in naming brands and products alike. They’ve curated and organized an essential list of tools and resources that we at the Studio have considered a miracle on more than one occasion.

Koto and their newsletter OFF-BRAND has an exhaustive start-to-finish piece on the pursuit of naming. We just scratch the surface here, but they really went in. They also share the same enthusiasm for the naming genius of Liquid Death.

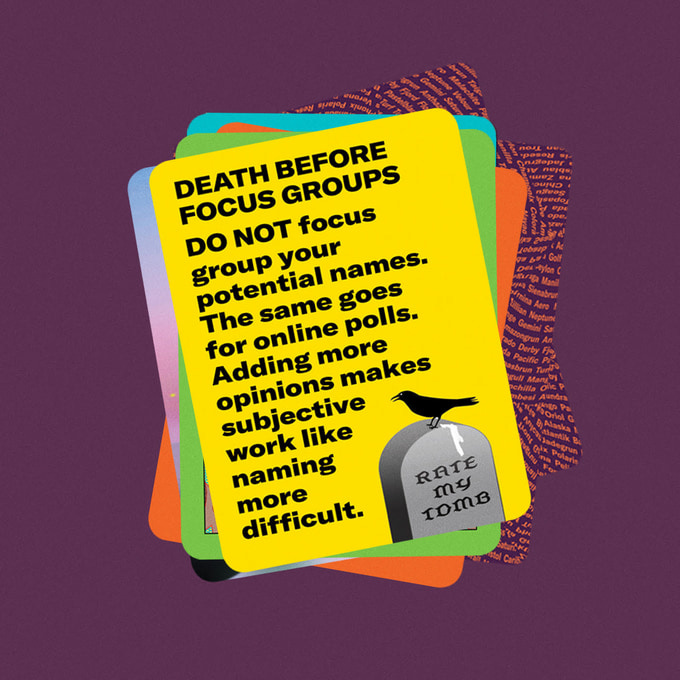

Altman, alongside his other pursuits, also created Go Name Yourself — an interactive 90-card deck to guide any naming process.

So where does all of this land us? Are we running out of names? Do names even matter? How can we possibly move forward from here?

Naming is a territory steeped in subjectivity, meaning there are hardly right and wrong answers. As you approach naming anything, a large determining factor of success is how well you’re able to navigate, and become comfortable with, that subjectivity.

It’s also important to understand the context, and where you sit within your environments. Some brands and projects exist and are born out of naming strategies, like Zappos or 1-800 Flowers. These are organizations that live and die by their naming real estate. While this is a great brand strength if available, it is not the reality for most of us starting new ventures or revisiting old ideas.

Ultimately, naming is just a piece of the puzzle in the larger brand picture. If naming can’t be the ownable and definable element of your brand, then it’s in your best interest to make other elements, like typography, color palette, or messaging proportionally carry more weight.

That being said, we find naming to be in many regards the final frontier of branding.

Typefaces, color palettes, and even brand claims and taglines can be easily repurposed and adopted by direct competitors, but a name is defensible, evergreen, and hard to copy.

Maybe the question then isn’t whether we’re running out of names, but whether we’re still willing to go to great lengths to look for them.

But we’re curious: what do you think? What names have stuck with you? Do names even matter anymore? Leave your thoughts in the comments down below and let’s discuss 💬

Thanks for reading

Findings is a project by Mouthwash Studio, a design studio centered on new ideas and defining experiences. Learn more about what we’re doing with Findings here. In the archive, you’ll find all our work to date surrounding this project.

This publication is 100% free and is supported by your time and appreciation. If you liked reading this, please share it with somebody who you think might also enjoy it.

Is there something we should cover? Respond to this email or send us a message at findings@mouthwash.co to get in touch.

Names still matter to me! Love the quote from Eli “a name is part of the gestalt of a brand” - I’ve got an article about my naming practice and philosophy here https://troycurtiskreiner.medium.com/creating-a-brand-name-people-love-silks-naming-best-practices-9e5e1b3a9d4d

Ps: I named Strawberry Western, check em out🍓🐎