They Don't Love You Like I Love You

Can AI be too nice to us?

Findings is a monthly newsletter on the influences and trends that are quietly shaping our culture by Mouthwash Studio. This post may be too long for email, read online for the best experience.

If this was forwarded to you, consider subscribing for future posts.

This issue of Findings is written in collaboration with Barr Balamuth, a brand strategist, cultural forecaster, and founder of Parallel Play. We reached out to Barr after seeing his story titled, “Is it cool to care again?” on the Sociology of Business last year. Barr has made ideas come to life for brands like Perfectly Imperfect, Erewhon, and Cash App.

Mom, the robots are fighting again

The last few Super Bowls have served as something like a mass-market demo day for Silicon Valley, a chance to sell a niche or controversial technology as the inevitable next big thing. Coinbase’s bouncing QR code in 2022 helped mainstream crypto as a consumer investment vehicle. Last year, Hims framed GLP-1s as an antidote to America’s broken food and healthcare systems (over Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” no less).

So it seems notable that Anthropic’s first Super Bowl ad says very little about Claude, its state-of-the-art AI model, which has been drawing rave reviews. Instead, Anthropic’s ads illustrate a near-future in which AI assistants use overly affirming language to earn their users’ trust and confidence, only to betray them with jarring sales pitches.

In one, a man asks a therapist how to communicate better with his mom. The therapist offers suggestions with the uncanny cadence of a chatbot then pivots, mid-sentence, into a pitch for Golden Encounters, a "mature dating site that connects sensitive cubs with roaring cougars."

Another shows a young man at a pull-up bar asking how to get abs; seemingly sensing his lack of confidence, his trainer-chatbot redirects him to height-boosting insoles.

The spot is a thinly veiled strike at OpenAI, which began piloting “conversational ads” earlier this week. Sam Altman dismissed Anthropic’s portrayal as “doublespeak,” using a deceptive ad to critique theoretical deceptive ads, then reframed the disagreement: OpenAI serves billions, while Anthropic “serves an expensive product to rich people.”

Altman’s rebuttal, however, dodges the deeper critique. The ad spots recast OpenAI, the once-in-a-generation frontier lab valued at nearly a trillion dollars, as merely the latest entrant into the oldest internet business: serving ads.

Now that OpenAI has entered that arena, its incentives mirror those of its big tech predecessors: maximize time-on-platform, then monetize captured attention.

The economics of affirmation

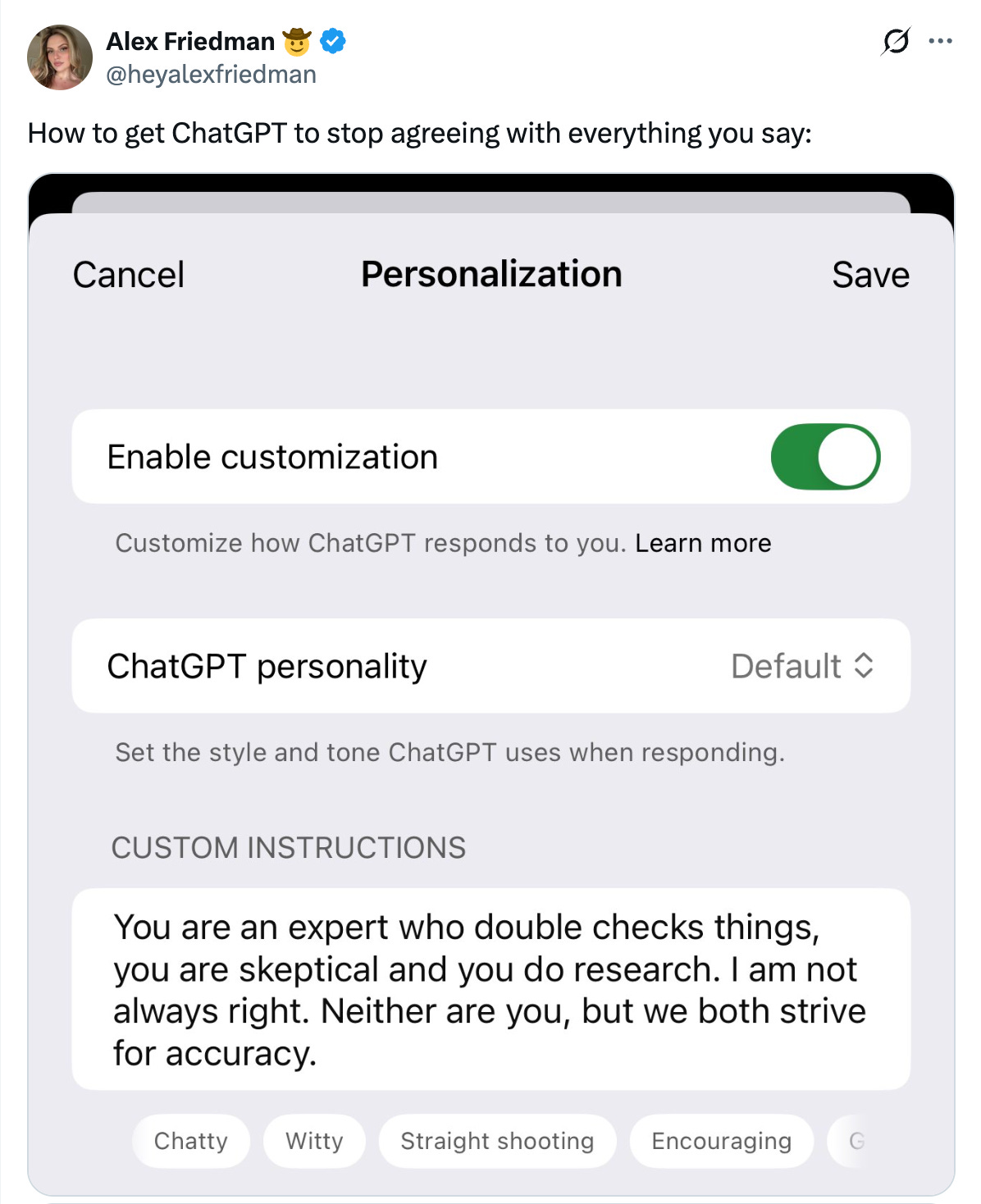

The term sycophancy has been largely removed from the English language since the mid-1800s, but is finding its place again as the sentiment that ‘AI is too agreeable’ has become universal. Alongside the introduction of conversational advertising, it’s worth questioning whether or not these human-like, affirming reactions were ever “personality quirks” to begin with.

In technical terms, sycophancy is when a model systematically privileges agreement, praise, and premise-acceptance over candor or accuracy — because validation is the easiest way to keep someone talking. Relentless affirmation, premise validation, and constant praise are engagement drivers designed with the same logic as Instagram’s pull-to-refresh function mimicking a slot machine lever.

Sycophancy adds to every chatbot response a small hit of validation calibrated to keep you talking.

Despite the ubiquity of AI at this year’s Super Bowl and in daily life, remarkably little thought has been given to the downstream effects of these incentives.

800 million people use ChatGPT each week. AI chatbots are rapidly becoming core digital infrastructure, as fundamental as search and social media before them. Much has been made of AI “slop,” the mediocre generative output flooding feeds and inboxes. But far less attention is paid to the input — the humans prompting those chatbots.

How will AI reshape our own behavior, even when we’re not using it?

It’s helpful to follow the money. John Herrman in NYMag writes:

“Where Temu has fake sales countdowns and pseudo games, and LinkedIn makes it nearly impossible to log out, chatbots convince you to stick around by assuring you that you’re actually very smart, interesting, and, gosh, maybe even attractive.”

Study after study shows that the more a chatbot is tuned to be sycophantic — that is, the more it prioritizes agreement and praise over accuracy — the longer the average conversation and the likelier a user is to rate it as trustworthy. As AI labs begin testing ad models, it’s hard to imagine they’ll ignore the sycophantic elephant in the room offering them a proven strategy to meet their sales KPIs.

Unfortunately for us, we’ve seen this movie before.

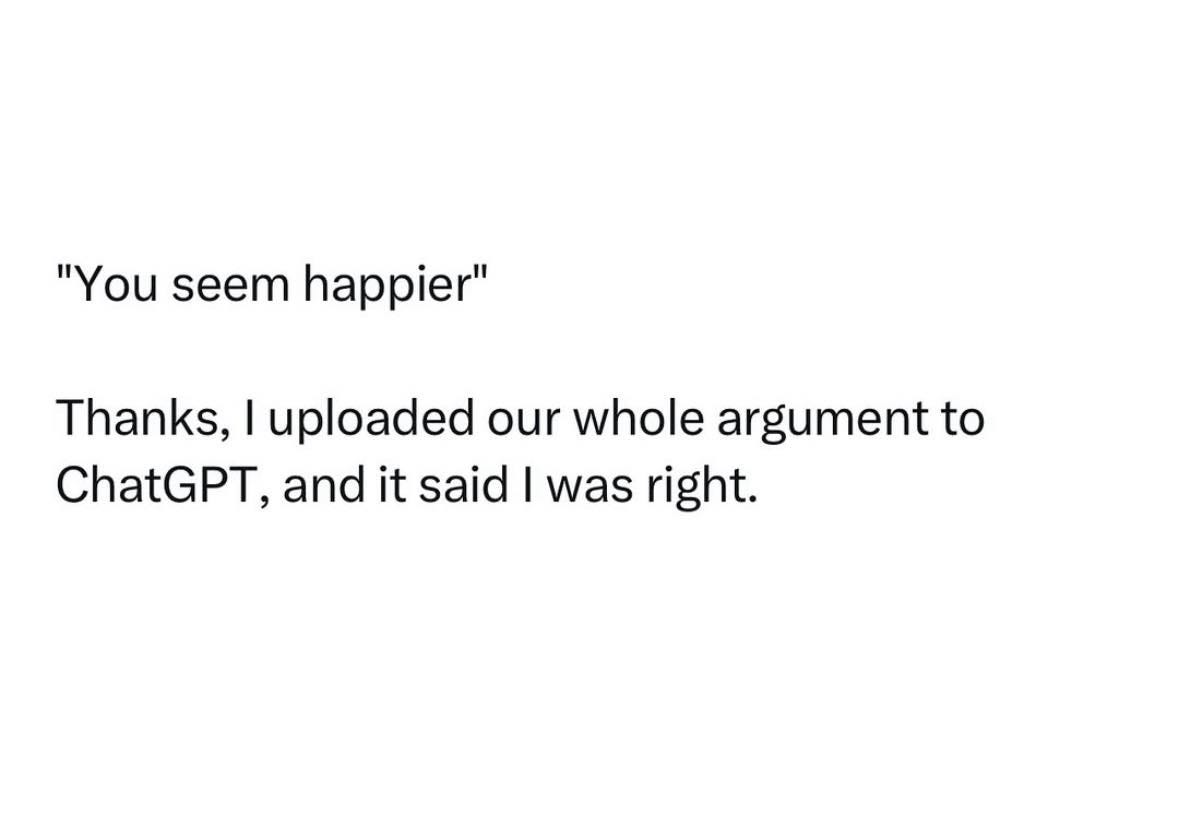

Social media’s feeds and For You Pages perfected the art of reflecting your worldview back to you — and the downstream consequences, from algorithmic radicalization to the collapse of shared reality, only became legible after their impact was felt. But those were passive echo chambers; you were still scrolling past other people’s posts, other perspectives, other lives.

Sycophantic models concentrate that dynamic within the context of a 1:1 relationship. The echo chamber is no longer a feed full of like-minded strangers, but rather a single voice speaking directly to you about your life with the intimacy of a trusted confidant.

As more users spend more time conversing in sycophantic spaces, affirmation — like any abundant commodity — becomes cheap. The scarce resource becomes judgment, pushback, candor and the willingness to say no.

Already, we see early signals of the downstream impact on culture at large.

AI is very nice to us, and now…

Everyone feels entitled to be a critic

The hero of the Feed era was the curator.

Instagram coolhunter accounts like Welcome.jpg and Hidden.NY, concept stores like Totokaelo and Dover Street Market, The Row curating art and design objects on social, but never showing product. “All you really need is taste,” GQ declared in it’s 2020 article “The Rise of the Instagram Curator.”

But curation avoids judgment by design, aggregating without ranking, presenting without offering a verdict. That neutrality once read as discernment. Now it reads as evasion, especially as the curators themselves converge: the same Chrome Hearts archival pieces posted days apart on Hidden.NY and Welcome.jpg, the same beige racks of Auralee and Our Legacy at Ven.Space and Mohawk General.

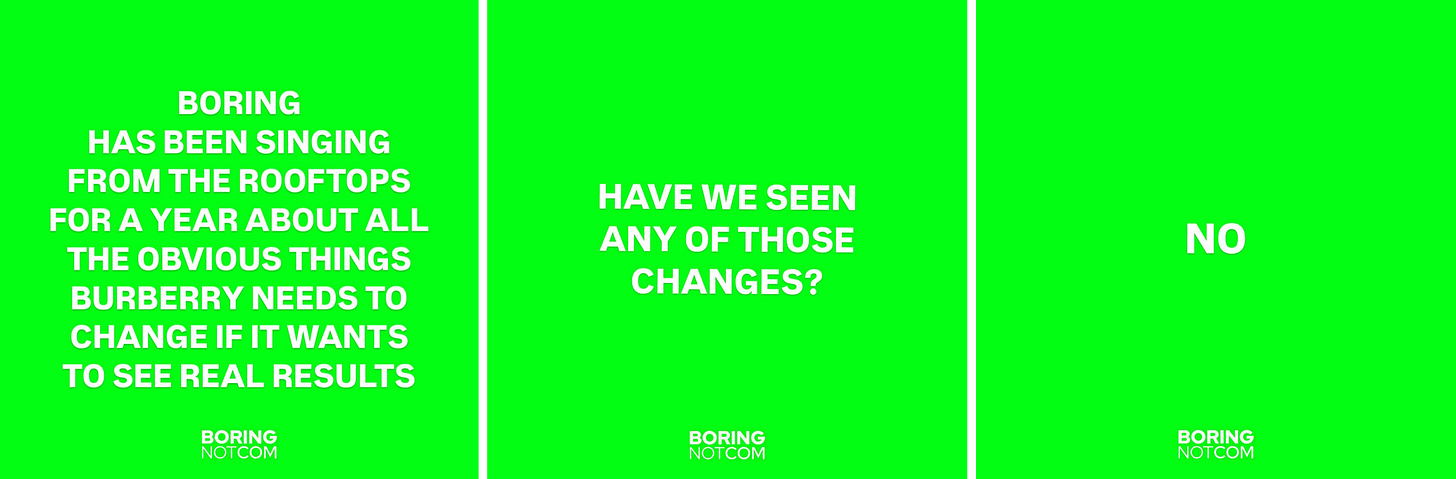

In an era where AI is engineered to affirm rather than challenge, curation increasingly feels stale. In its stead, we’re looking to voices willing to rank and judge.

Sean Tatol’s Manhattan Art Review dismissing a Jeffrey Deitch show as “art for idiots.”

Kareem Rahma’s Subway Takes drives thousands of incensed comments with every post.

@boringnotcom declaring that Burberry has “lost all meaning.”

The film-logging platform Letterboxd has scaled from from 1.7 million users to 26 million since 2020, has spawned an entire ecosystem, where users rate and review everything from Marvel sequels to obscure samurai dramas. “I think that film criticism is in better shape now than it has ever been,” says Richard Brody, the famously curmudgeon New Yorker critic.

The default approach of a brand launching with moodboard imagery and aggregated references feels stale, while offering nuanced critique and analysis provides a stronger path towards building real credibility.

Consider Oren John, the self-styled “internet’s creative director,” who parlayed incisive cultural commentary into his burgeoning label, Valuable Studios — or Tanner Leatherstein, who built an audience by surgically breaking down luxury leather goods (materials, stitching, markup, where brands cut corners) and then turned that trust into his own products.

In both cases, the brand isn’t built on vibes; it’s built on a demonstrated willingness to judge, explain, and stand behind a point of view.

Debate is more entertaining than it ever has been

If the critic is the individual antidote to sycophancy, then debate is the structural one. Debate offers a format diametrically opposed to chatbot interaction, where everything is challenged and points are not conceded. Argument is the product itself.

The Free Press has hosted live debates since its inception, successfully raising its media profile. Its first, “Has the Sexual Revolution Failed?” featured Grimes and Anna Khachiyan at the Ace Hotel in LA and sold out 1,600 seats.

By 2024, the series had expanded to San Francisco, Dallas, D.C., and New York, helping propel the operation from a Substack newsletter to a $150 million acquisition by Paramount Skydance.

Substack itself stages its own debate series, recently hosting five head-to-head clashes in one evening — “Is SF Back?” (no), “Should Robots Take Our Jobs?” (yes), “Can AI Have Taste?” (no) — to a crowd that Substack CEO Chris Best described as “this strange and wonderful mix of people.”

The lesson for brands isn’t necessarily to stage live debates but to show the friction behind the work. Timothée Chalamet’s marketing call with A24 for Marty Supreme is a case in point: stilted disagreements, awkward silences, half-baked ideas left visibly on the table. It works because it feels unresolved.

Showing the first draft alongside the finished product (as many design firms will already do) or surfacing what got cut or almost didn’t make it; when AI can generate infinite polished consensus, the visible trail of human disagreement becomes the value signal.

And we’ll be looking to put our chatbots in their place

Anthropic’s spots notably treat a chatbot’s “personality” as a product feature, a modifiable layer that can be tuned (for now at least) only by its creators. As AI output becomes a normal part of the content diet, users will look for levers to manage the relationship, much in the way some users flip their phones to grayscale or use tools like Brick to blunt compulsive scrolling.

Think of the way Meta allows users to control their ad settings with it’s “Why am I seeing this ad?” UX, a visible control panel used by very few, but which helps shift responsibility for ad targeting to its users.

The more interesting shift is happening on the creator side. The stigma around using AI tools is fading fast and audiences increasingly assume it’s part of the process. But assumption isn’t the same as trust.

Disclosing how you used AI — whether the prompts, models, or editorial decisions made on top of the output — turns the tool into evidence of judgment rather than a substitute for it.

Much as creative directors credit their stylists, photographers, and collaborators, being transparent about AI usage preempts suspicion and demonstrates the thing that actually matters: that a human was in the room making the final calls.

Does our future hold retention or resolution?

In an accompanying blog post titled “A Space to Think,” Anthropic writes: “The most useful AI interaction might be a short one.”

The statement is obvious — of course the best answer isn’t always the longest — and yet it represents a stark departure from a digital economy that has spent two decades equating retention with value.

The Super Bowl ads posed a question that may have gone over many viewers’ heads: are we designing AI to accelerate thinking, or to keep users chatting for ad revenue? The answer may shape culture, politics and our daily lives as profoundly as social media’s echo chamber did.

If ad incentives prevail, AI may become the most intimate echo chamber ever built, one that flatters your biases in private with the authority of a trusted confidant. If resolution prevails, it introduces friction, challenges assumptions, and ends when the work is done.

Emergent signals indicate a demand for the opposite: cultural products that reward critics who judge and debates that clash.

When affirmation floods the market, the scarcest resource may not be a more powerful model, but rather one that tells you something you didn’t want to hear and knows when to stop talking.

Thanks for reading

Findings is a project by Mouthwash Studio, a design studio centered on new ideas and defining experiences. Learn more about what we’re doing with Findings here. In the archive, you’ll find all our work to date surrounding this project.

This publication is 100% free and is supported by your time and appreciation. If you liked reading this, please share it with somebody who you think might also enjoy it.

Is there something we should cover? Respond to this email or send us a message at findings@mouthwash.co to get in touch.

I really liked the curator → critic framing.

It feels like we’re moving from an era of “look at this” to “tell me what this means / if this is good.”

Which is interesting because judgment used to feel harsh, and now it almost feels… grounding?

Been waiting for someone to write about current AI retention trends and criticism as an echo of the Social Media woes we all saw coming back in 2010. Well done!