A Brave New (Frictionless) World

What did we lose when everything got easier?

Findings is a monthly newsletter on the influences and trends that are quietly shaping our culture by Mouthwash Studio. This post may be too long for email, read online for the best experience.

If this was forwarded to you, consider subscribing for future posts.

I. The year-end emerging pattern

Over the last six months at the Studio, we’ve found ourselves circling similar conversations across all our projects. It seems, no matter the circumstance, one word unfailingly creeps up: Friction.

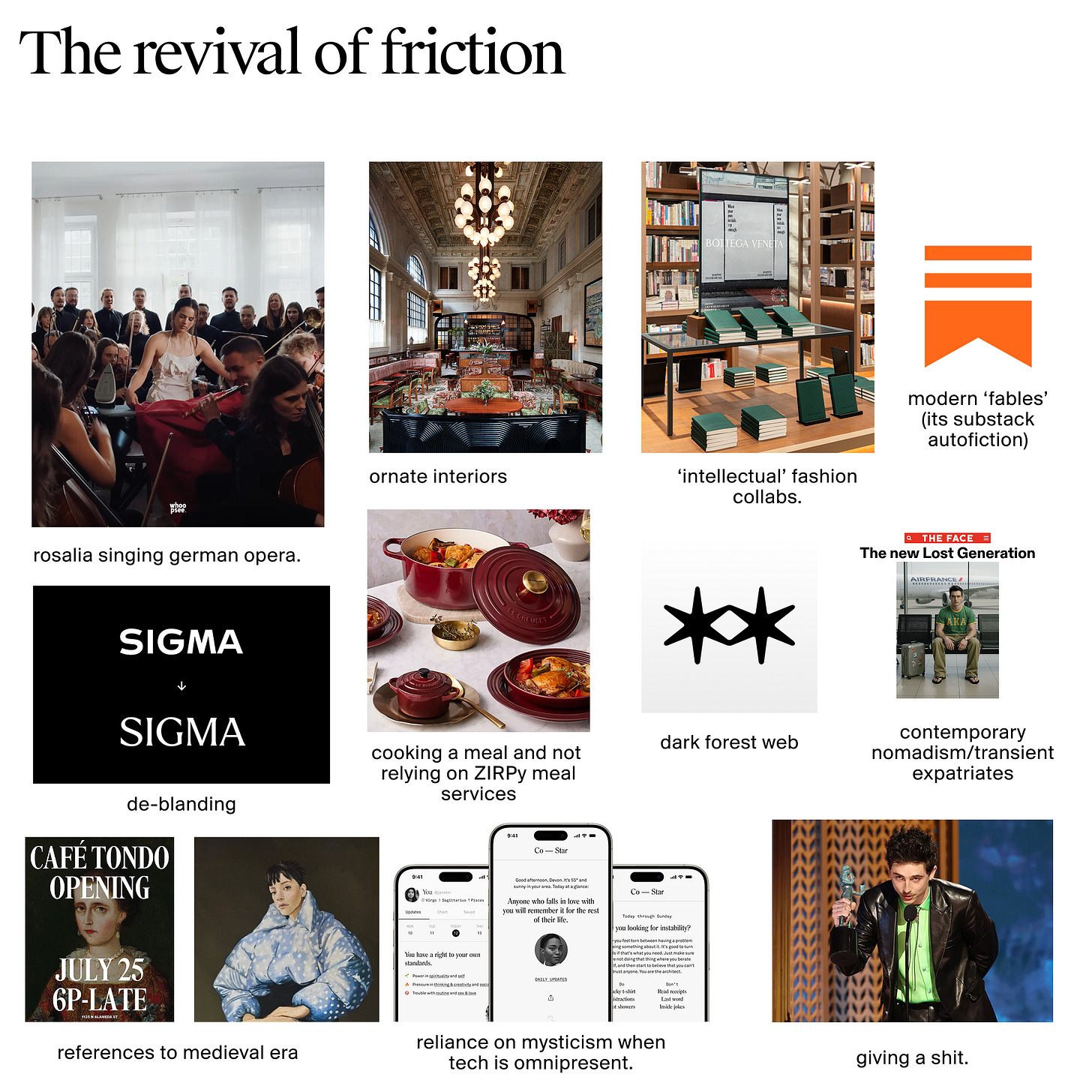

You’ve probably noticed it too. Rosalía singing German opera. Film’s recent obsession with centuries-old literature of longing, turmoil, and neglected duty. Jonathan Anderson’s painstakingly delicate 17th-century-inspired collections at Dior. Across culture, bright flashes of all things opaque, ornate, and difficult have been emerging as a visual and conceptual pushback against the slick, smoothed-out realities of our 21st-century condition.

It seems, finally, that the sad beige baby has been thrown out of the bathwater.

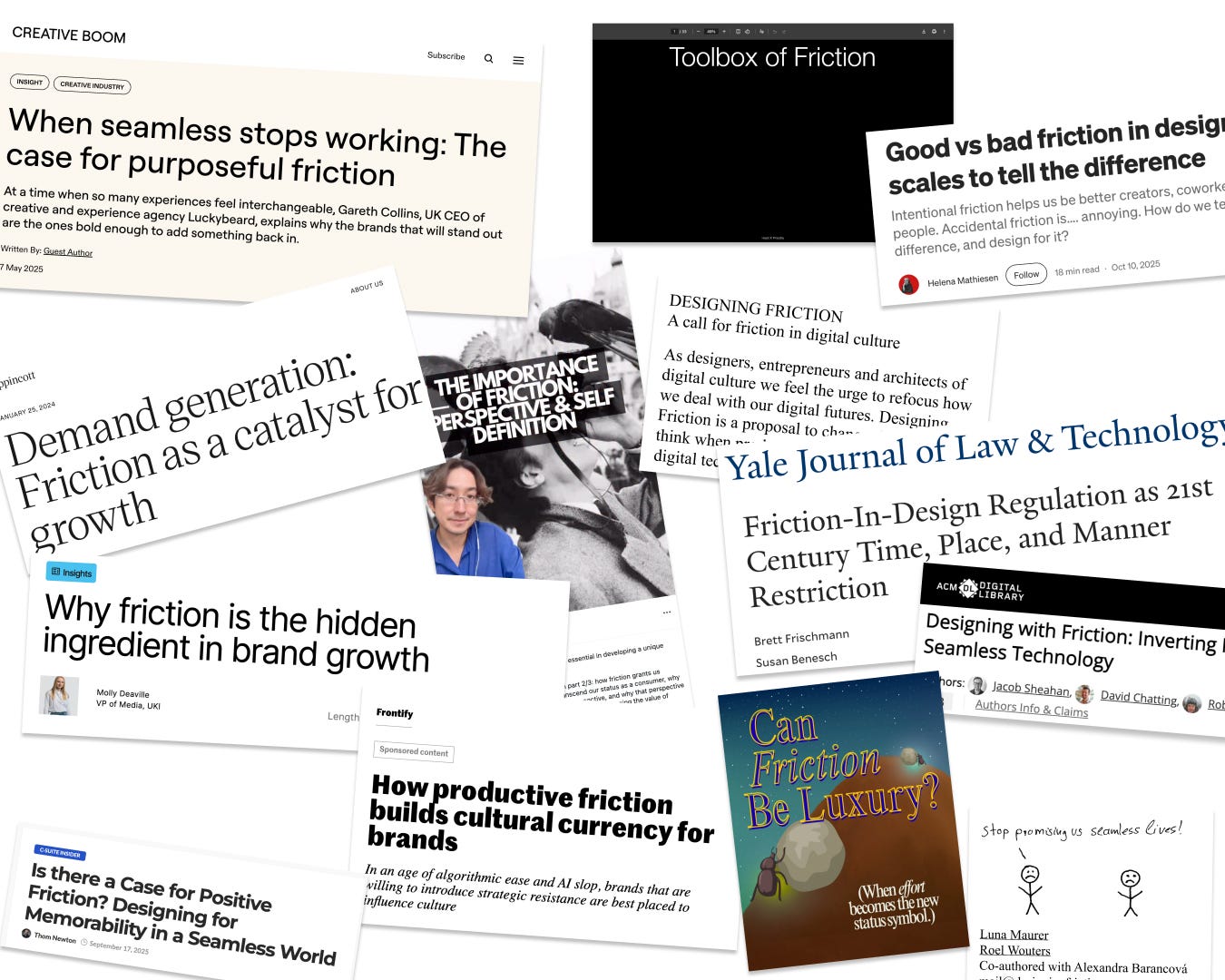

At the same time, a torrent of trend reports and year-in-reviews will soon and certainly flood your feeds and inboxes. No doubt this year, many of them will talk about friction and the resulting visual response that will come to dominate across design, interiors, and commercial creativity in 2026.

As for us, we’re less interested in telling you what color you should use on the front cover of your zine, and more fascinated by what’s behind this coming paradigm shift. Why is the pendulum swinging from a design culture of ease, simplicity, and seamlessness, to something more sticky and textured? Better yet, who (or what) decided to let it go?

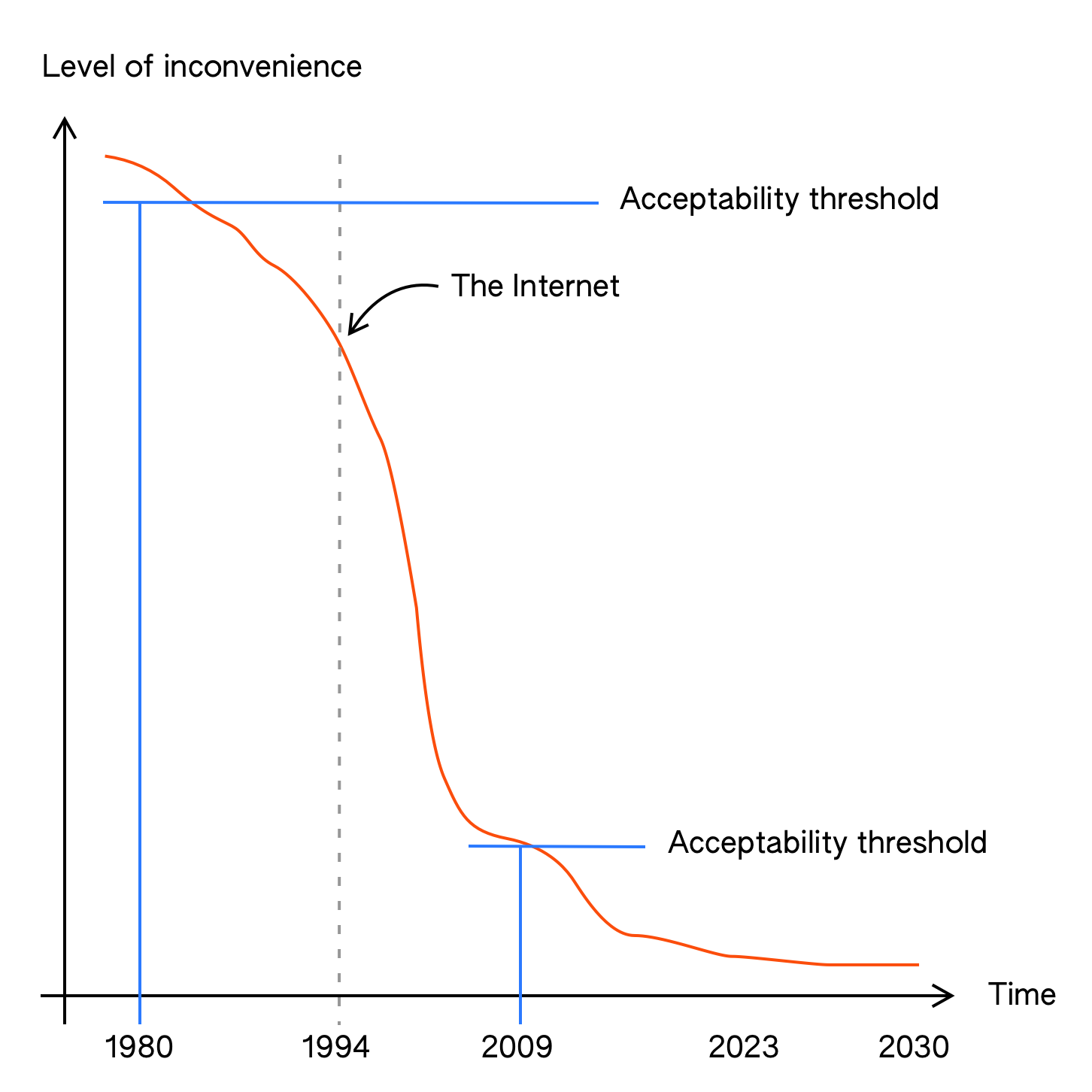

Friction’s role in design and brand theory is anything but new. Historically, our industry has been oriented towards the seemingly simple task of developing products or experiences that make life better. And for a long time, “better” meant easier, more pleasant, and more efficient. Friction-less.

But as we near the apex of seamless, friction-reducing design, have we really arrived at “better”? Letty Cole’s breakdown of The Detail Deficit presents our current reality as an affirmation of predictions from the likes of Adorno, Horkheimer, Loos, and Walter Benjamin. This reality, depending on your disposition, is either a stark, modern utopia, or (more likely if you’re reading this) a disappointing inevitability of an increasingly mass and commercialized condition.

But we’re optimists. And from action, we anticipate reaction. We partnered with Cultural Strategist and Researcher Edmond Lau to investigate what we hope to be a meaningful inflection point. We’re out to understand why friction matters, what makes friction meaningful, and how brands can use it to make this world a more interesting place to be again.

II. A Frictionless World

If you happened to pay attention, you might remember your high school physics teacher illustrating the dangers of a frictionless world: cars can’t come to a stop, walking becomes physically impossible, molecules cannot bind together, and our planetary orbit shifts so drastically that our solar system ultimately unravels. In a frictionless world, everything keeps sliding, drifting, colliding and dispersing into utter instability. Nothing is anchored, so nothing is sacred.

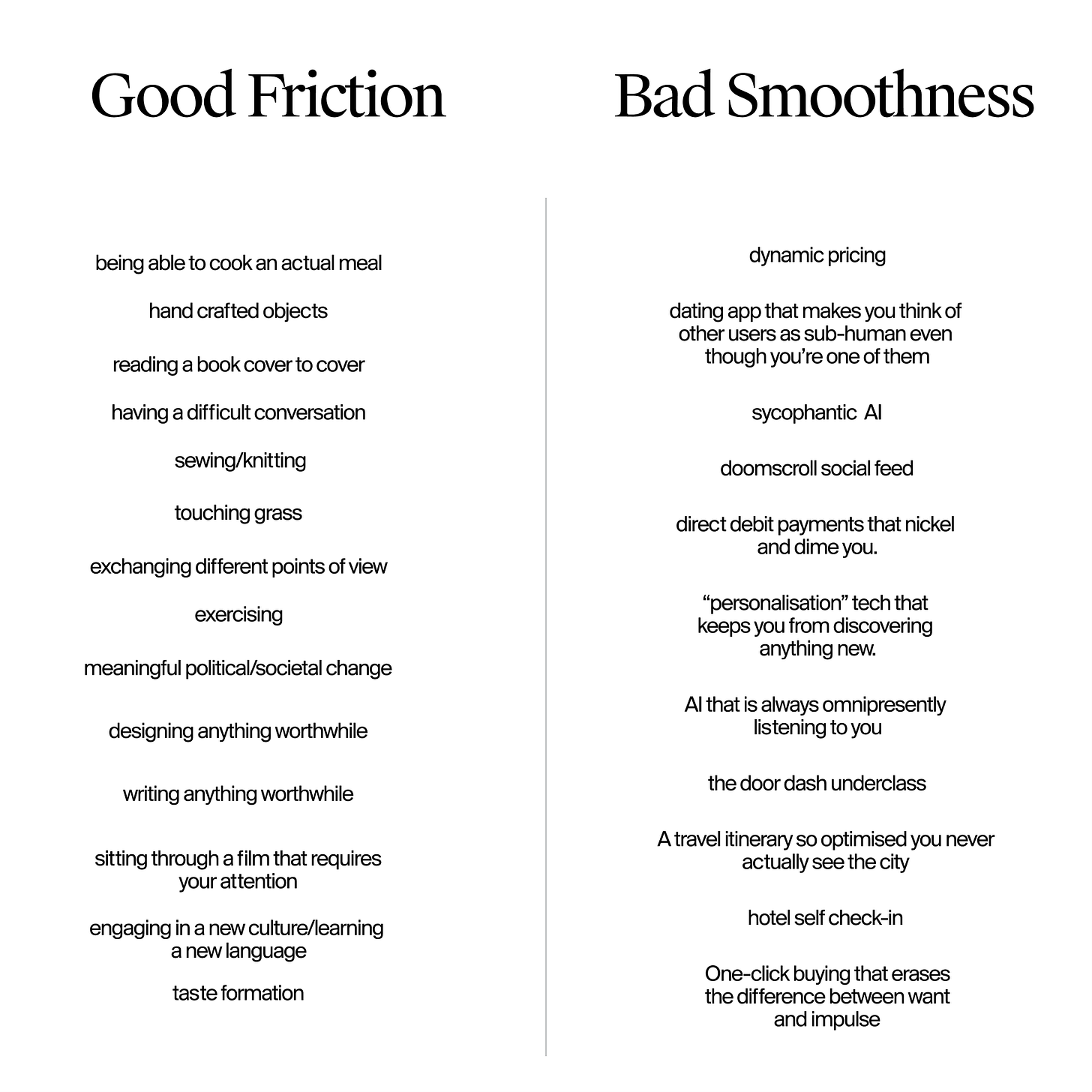

It’s a bit ironic then, that for so long we’ve found ourselves designing seamless experiences, fighting against friction, and optimizing for efficiency just to come to the realization that efficiency can also be weirdly bad. When attempts to reduce friction fail to consider human realities, you get incredibly broken, janky experiences.

That jankiness is perhaps best articulated by this quote from contemporary philosopher Maya B. Kronic, referenced in Daniel Felstead and Jenn Leung’s video essay, Welcome to Jankspace, Babes:

“Jankspace is how you feel when you just used Touch ID to access your keychain and you’re desperately reaching for the power cord to plug in your phone and get it powered up so that you can get the code from the OTP text message and activate your hotspot so as to get the email confirmation for a password change in time so you can access the cloud storage where you keep the scan of your ID that’s required by the payment app that just asked you to verify the microdeposit sent to your bank so you can buy some shit you saw on Instagram at 2 a.m. after you’d been scrolling liking and subscribing all night.”

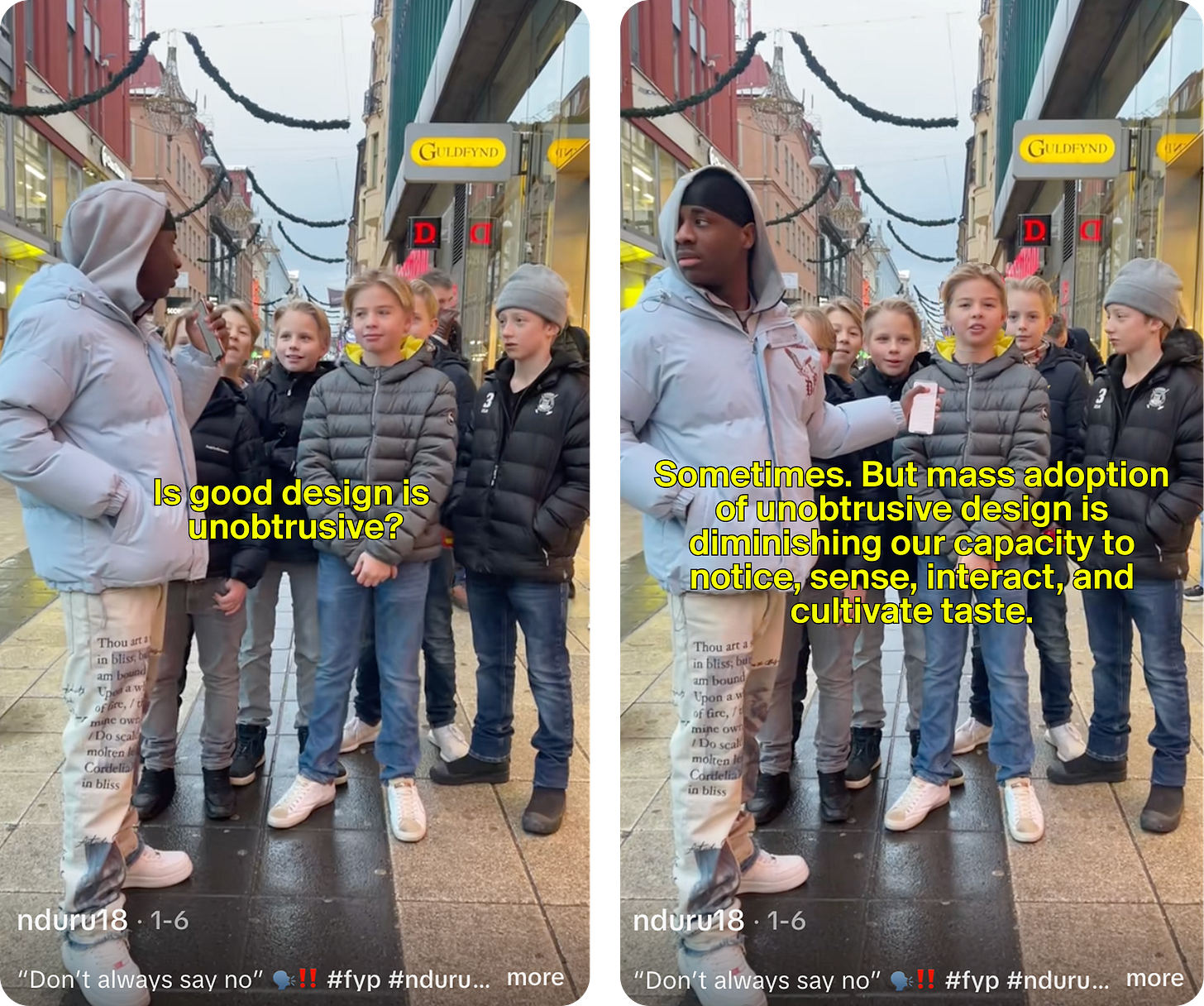

This idealistic vision of seamlessness tends to have a shoddy practicality once it’s brought down to earth. It feels as if Dieter Rams philosophy of good design is “invisible” has become perverted by Silicon Valley’s particular brand of surveillance capitalism—justification for the always-on observation, tracking, measuring, and predicting of every consumer behavior. You can’t even look at an object without getting served up an Instagram ad for it.

These forces are clouding our human tendency to evaluate, discern, and recognize effectively. And this clouding is being wreaked intentionally by entities whose aim is to feed our unchecked impulses—and to do so from just outside our periphery.

You can’t bite the hand that feeds you if you don’t see it in the first place. Based on this, it’s hard to argue that invisibility has anything to do with good design, presenting a real conflict of interests for any brand or company that is valued by their cultural and creative output. Handcuffed to an industry obsessed with optimization, is it better to be authentic, or to be efficient?

The very first piece we put out for Findings discussed a very similar dilemma. Opposing Convenience, made in collaboration with Malte Müller, was part of a larger report of Annual Findings from 2023, and looked to establish ways to find merit and reward in actively resisting efficiency and optimization in our experiences.

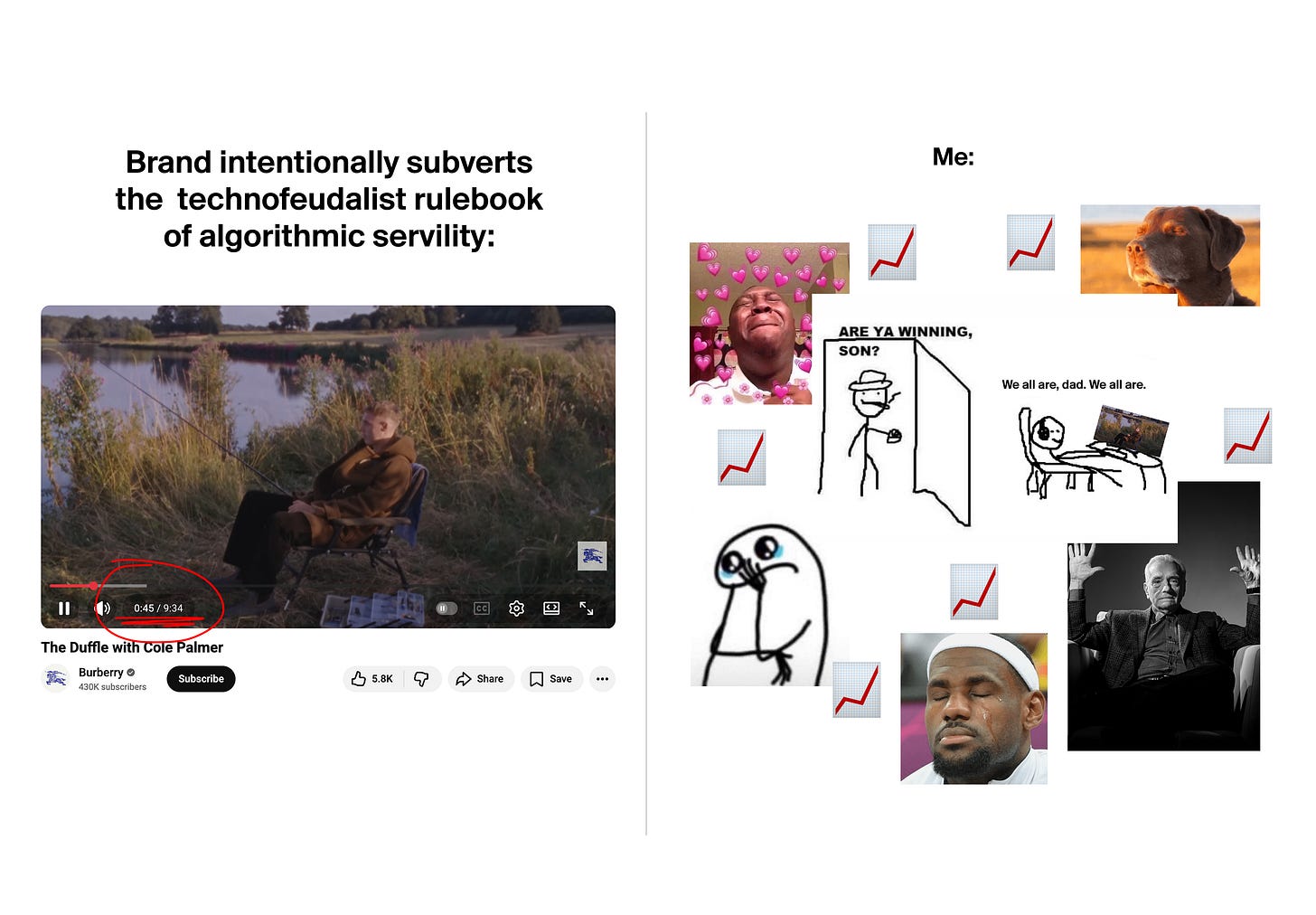

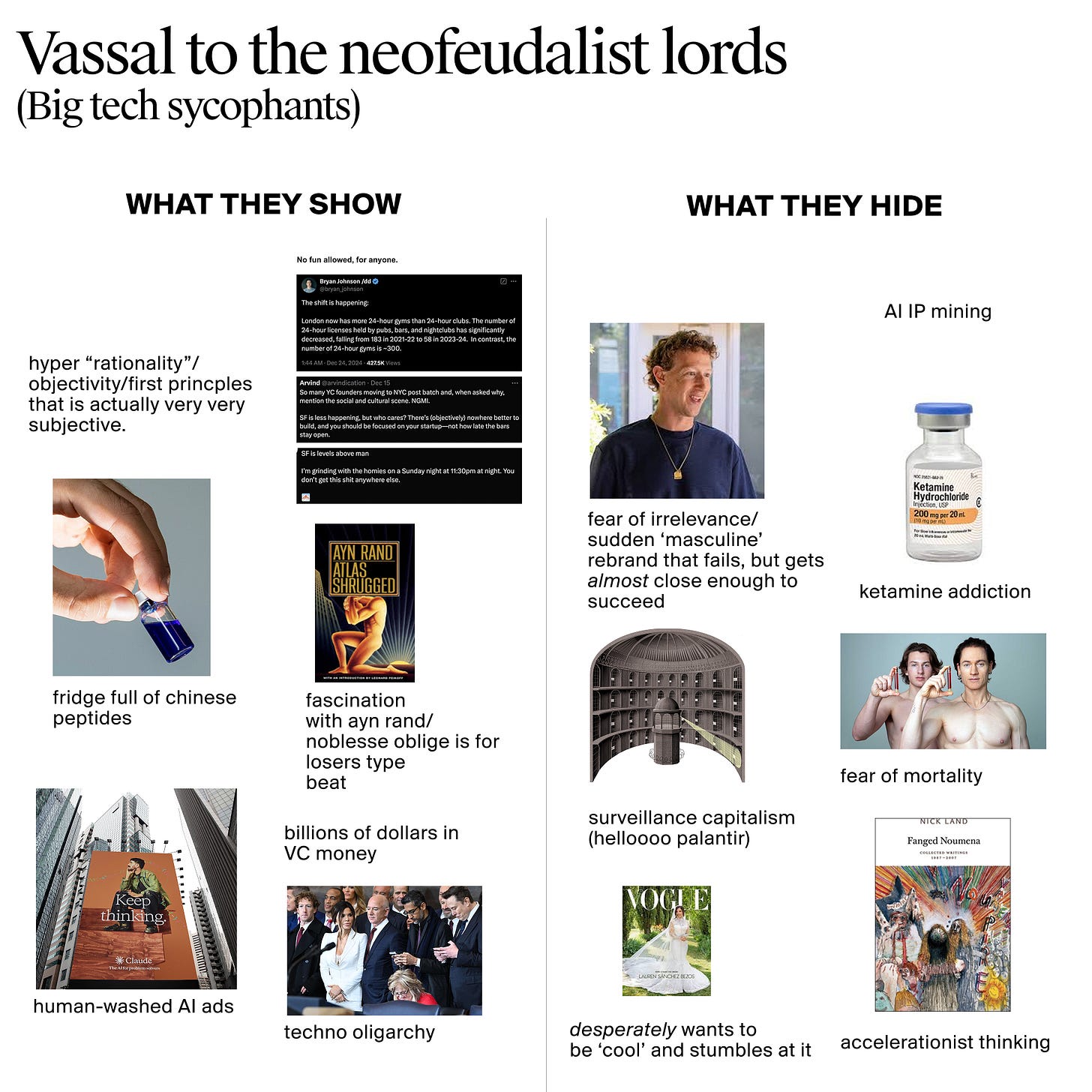

This strange material obligation to optimization that so many brands have come to know, and resent, hints at a sort of modern-day feudalism. Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s former Minister of Finance, is a leading voice on this techno-feudalist reality; it’s one where in Big Tech owns the land (in this case, digital platforms) upon which brands and people must produce (make, sell, and distribute their content, goods, and services).

Despite not producing anything, these techno-lords get a huge cut on everything grown on their land. Amazon storefronts are a prime example of this dynamic in action. By no means is it a stretch to assign this pursuit of efficiency, of over-optimization and frictionlessly invisible design, as the flower bed for technocracy today.

There are surprisingly-obvious analogues for our newfound feudal condition. In today’s feudalism, AI is our God, the Algorithm, our church. Food scarcity comes in the form of overpriced small plates. Podcasters are the town crier and shitposters are the court jester. Layer in the real-world impact of tariffs, rising inflation, a stagnant job market, and both domestic and international conflict, and it’s all there.

The technorati, of course, attempt to mask their rampant pursuit of efficiency by cosplaying industrial monks. The archetypes are comical enough on their own, even without a punchline. Engineers on high six-figure salaries sleeping on a mattress on the floor. Founders who performatively, but unproductively, toil away into the early hours of the night.

They perform an absurd LARP of no-frills efficiency that is intended to persuade others of not only their successes, but of their superior virtue that, you too, should emulate. Never mind that Bezos’ yacht was so large a Dutch bridge nearly had to be dismantled just to let it through.

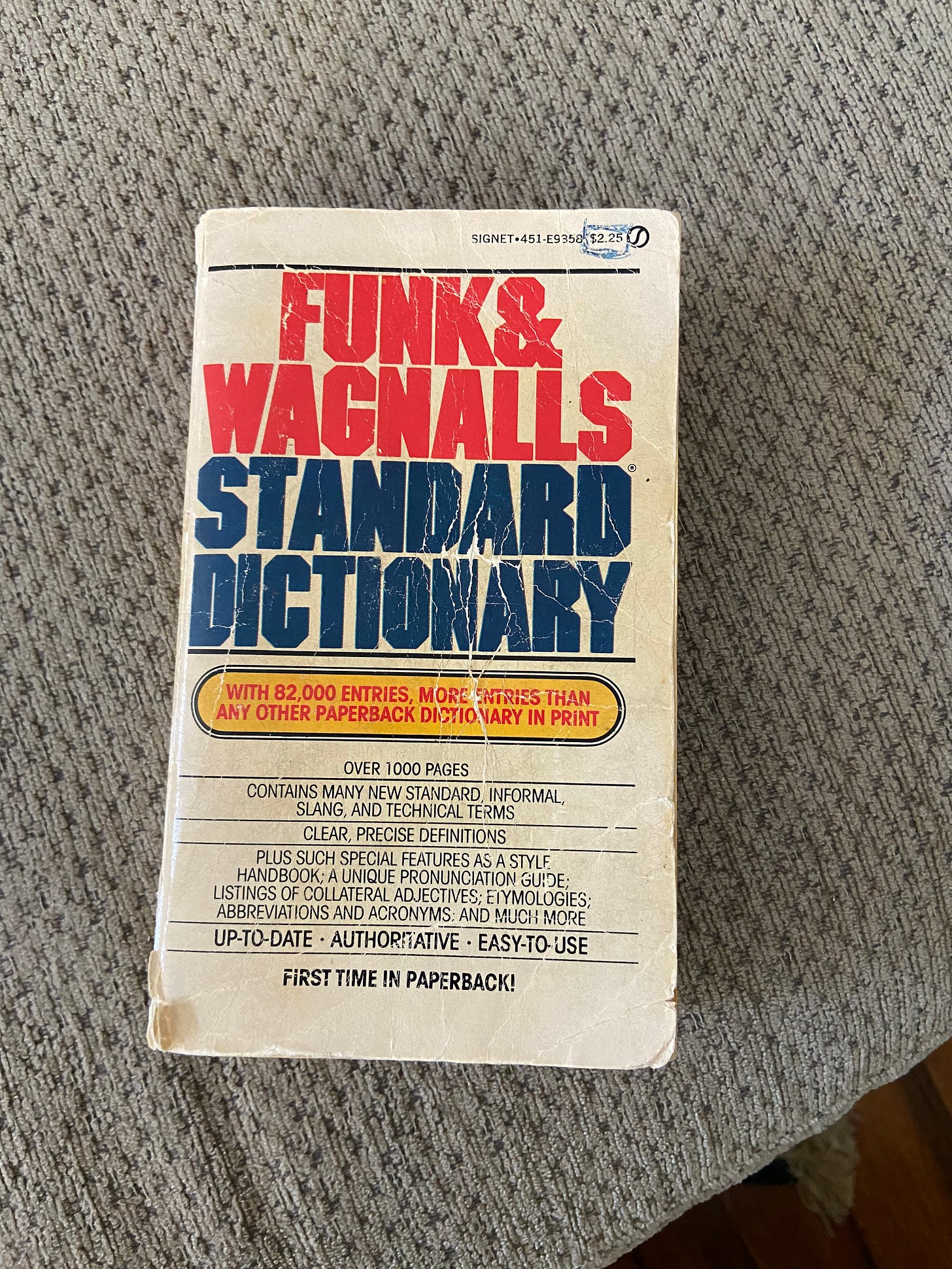

In the face of these anti-friction, techno-feudalistic conditions, it makes sense that we’re seeing a cult-like resurgence of “slow tech” as a natural rejection. Wired headphones, analog watches, and looking up a word in a physical dictionary are the equivalent of a middle finger to the techno-feudalist philosophy of efficiency. It’s how consumers today can arm themselves against these dark and invisible forces that swirl around them.

There’s a case to be made that against these invisible evils, design that is honest, conspicuous, and at times inconvenient, could now start to establish itself as not just good, but necessary.

But how might friction serve as an antidote to our mountain of AI slop? We see traces of it in the rise of de-blanding, of new-heritage emblematic design, and signet culture. But good friction isn’t simply an embellishment. It’s measured, and demands strategic implementation.

Introducing friction into design and experiences is like breaking in a new pair of shoes. At first, they give you blisters. But you persevere. In the pursuit of taste. Expertise. Sophistication. Style. Cultural signaling. It’s painful and restrictive in the beginning, but the payoff is that, in the end, they fit like a glove. Perfectly molded to your unique sole—yours, and yours alone. Common sense would have you buy a pair of shoes that don’t need breaking in. But we do it anyway, because we know it’s worth it.

So how do we give brands blisters?

III. Making Friction

There’s a common fallacy that brand friction means making things difficult for the sake of being difficult, which we wholeheartedly reject. In this regard, friction is misleading. The idea is not to make things difficult, but to go the extra mile. To put in the necessary effort. To spend that extra bit of time, energy, or dare we say…profit, to create real value for consumers.

The thing that makes Burberry a friction-forward brand isn’t the fact that they’re de-blanding their visual identity, it’s the fact that they produced a 9-minute long video of Cole Palmer where nothing happens. It’s refusing to shrug shoulders at shortening attention spans and challenging users to sit with tougher material. A blatant disregard for the playing field and how to “optimize” it. That’s where friction comes in.

The video didn’t break any performance metrics. It didn’t go viral. It didn’t have a moment. That’s not the point. The point is that we’re still here, talking about it, a year after it was made.

Even Apple is beginning to pick up on this dynamic. For the first time in over a decade, their design language is evolving to add things back in through Liquid Glass. Their product roadmap can best be defined by innovation via reduction, but this new synthetic layer that now sits atop everything else is a noticable shift towards friction, towards the visible. Even if that visibility is transparent, at best.

The desire to understand what performs well by the technocratic playbook, and to actively reject it in favor of a different direction is what friction looks like for brands today. The challenge then is not in the act of doing, but defining what meaningful friction looks like for your specific endeavor.

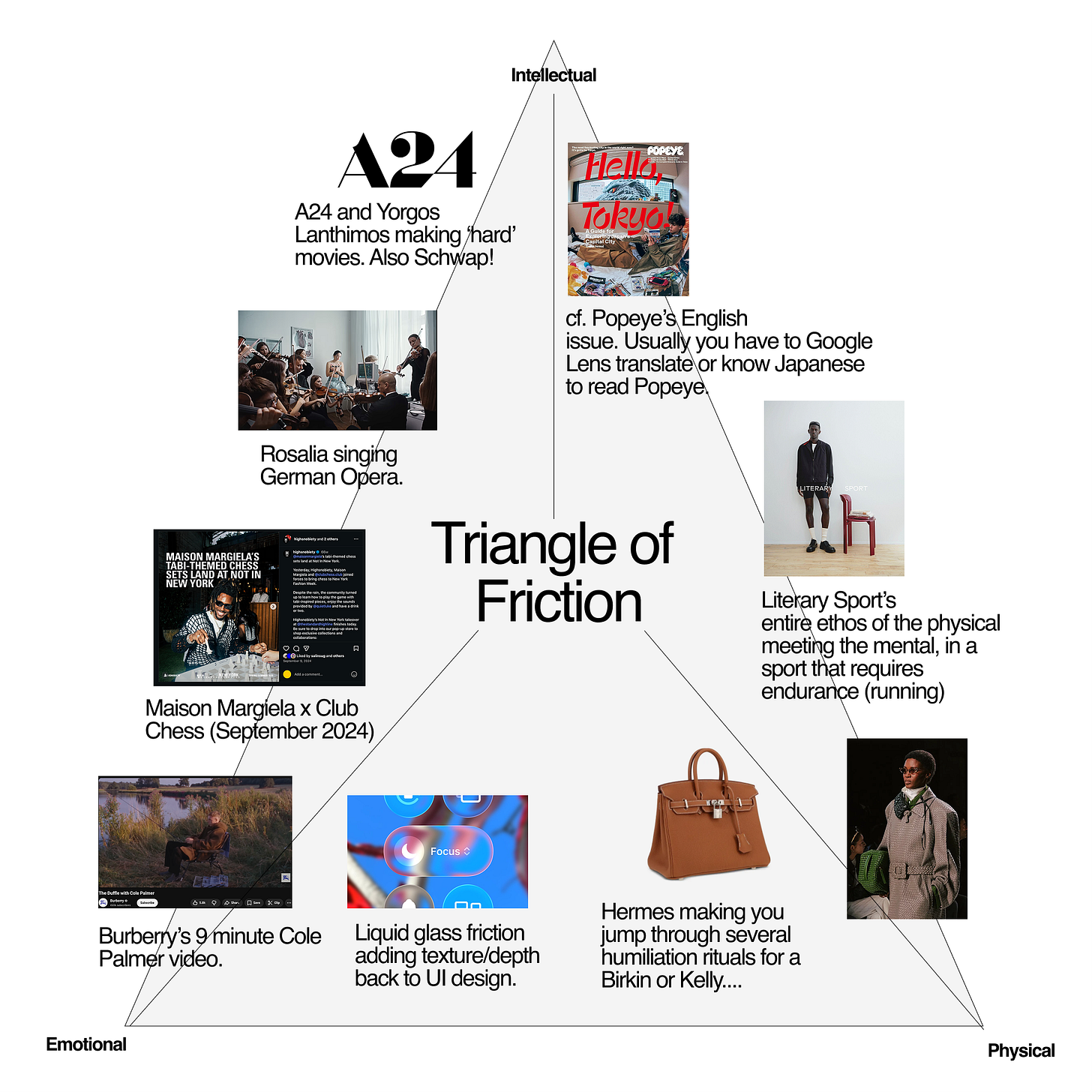

Friction alone won’t solve all your brand or design problems. It comes in good and bad flavors. But by breaking friction down into physical, intellectual, and emotional manifestations, brands can start to consider how to free their users from the shackles of doomscrolling optimizations and efficiencies. Designing Friction is a great aide in this process as well, outlining several practical translations for what this could look like in-situation for brands and experiences.

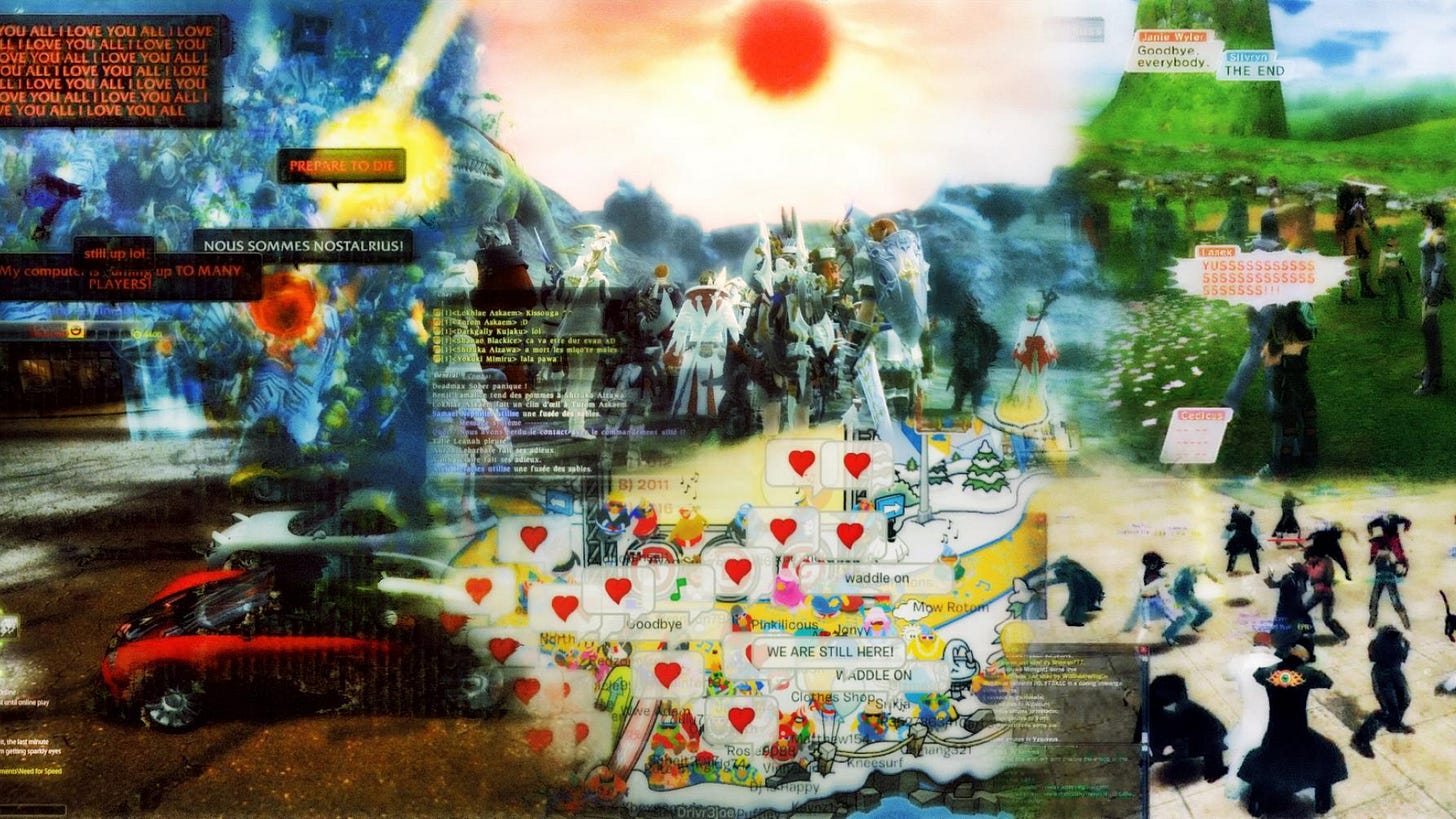

We expect to hear a lot more about friction over the next few months. Design and cultural output have indeed been unfortunate casualties of the optimization craze. Brands and graphic systems have started to blur together, emulating each other in an effort to appease the platforms that extort them. And the implications inevitably trickle down to the end users. Yet as we continue waking up to these conditions, we’re reminded that friction in and of itself is not the end goal, nor has it ever been.

Rather, friction is a mechanism that asks us to notice, to sense, to interact. It’s a tether to effort and patience. It serves as a gateway to thoughts and experiences that resist instant legibility. After all, the best things in life often demand concerted effort or acquired taste. It would be a shame if, in smoothing everything out, we lost the capacity to appreciate deeply or discerningly through effort and understanding.

In a frictionless world, everything just floats, drifts, and accelerates to no end. Friction makes people stop. But that’s just the first step. Once you have their attention, what will you do?

Thanks for reading

Findings is a project by Mouthwash Studio, a design studio centered on new ideas and defining experiences. Learn more about what we’re doing with Findings here. In the archive, you’ll find all our work to date surrounding this project.

This publication is 100% free and is supported by your time and appreciation. If you liked reading this, please share it with somebody who you think might also enjoy it.

Is there something we should cover? Respond to this email or send us a message at findings@mouthwash.co to get in touch.

How does working with OpenAI advance friction?

I loved this so much and I really hope we do continue to move in this direction of personality and authenticity and deblandness. I find the minimal trend that has dominated one of vulgarization.